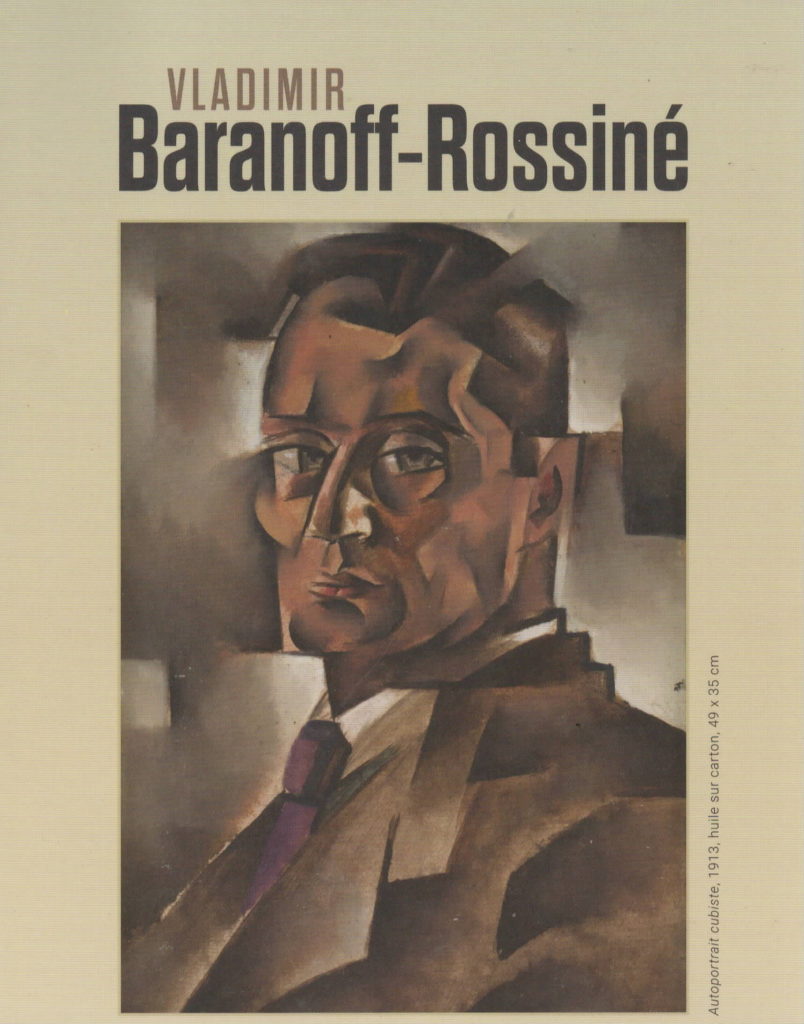

A MULTIFACETED GENIUS – BARANOFF-ROSSINÉ

EXPOSITION À LA GALERIE LE MINOTAURE

EXPOSITION À LA GALERIE LE MINOTAURE

(13MAI-29 JUILLET 2023)

A MULTIFACETED GENIUS

Vladimir Baranoff–Rossiné is an eminently representative example of the artist figure as it emerged in the twentieth century. Of course, it is Picasso who, starting in 1910, came to epitomise this image of the creator, a figure that was completely new in relation to all that had gone before in European art. Having rejected four centuries of renascent Renaissance academicism, having wiped the slate clean of conventional codes of representation, the twentieth century artist found himself condemned to a relentless quest for ever new processes and ways of apprehending nature or the world. He became Proteus, as André Malraux said of Picasso.

When we consider the whole of Baranoff–Rossiné’s oeuvre in its entirety, the striking thing, precisely, is its protean character, its succession of highly varied and sometimes overlapping periods, each so different in style that it is impossible to speak of “transition” or “evolution.” An alchemist of painting, a tireless experimenter, Vladimir Baranoff–Rossiné never stopped creating, inventing and finding original formulas. As a creator of his times, he never confined himself to a formula, constantly keeping his inventive genius on the alert, and although he left more than five hundred oils, drawings, watercolours and gouaches,[1] his activity did not stop there. In z letter he wrote to Robert and Sonia Delaunay from Ljän in Norway on 26 June 1916, he states:

“I am very busy, as I always have been and always will be, I live only by painting. The period of prolonged rest as well as the journey through Great Russia[2] have had a beneficial effect.

In painting, I am the same as before: and I will also die, as I am. I do whatever I want. And my struggle consists exclusively in fighting against the impossibilities that prevent the realisation of what I want. I paint academic studies and work in the field of chemistry, I study spectral analysis and the sun; I am also working on a piece with various materials, colours and forms. For me, painting is real life. The main thing is that what I do, I do with love, so much so that I enjoy it.”[3]

In these few lines we can sense the scope of the Ukrainian-Russian painter’s artistic activity: he practised traditional art (“academic studies”), scientific research into the laws of light (analyses of the Sun’s spectrum), and the invention of objects incorporating a variety of materials. Here we have the summary of Baranoff–Rossiné’s aesthetic concerns throughout his life: easel painting, technical knowledge and technological invention. To reiterate, this approach is typical of the twentieth-century artist for whom art as techne regained its character as an empirical, scientific, cognitive practice, something which secular academic routine had tended to obscure by limiting it to the framework of a single mode of apprehension of reality.

We can thus see that before the revolution of 1917 Baranoff–Rossiné was following the line that Robert Delaunay had been experimenting with since 1912–13, that of light as a material, retinal element of vision. In his desire to go beyond impressionism and neo-impressionism, which had focused on the effects of light, Delaunay turned to the sources of light, whose coloured wave-rhythms or, as we used to say before 1914, “vibrations in the ether,” had been made visible by science. In another letter from Rossiné dated 15 September 1916, written to the Delaunays from Kristiana, he says that he has studied Chevreul. This was precisely the subject of the Delaunays’ research.

The importance of the work of the nineteenth century French chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul for Delaunay’s research into light and colour is well known. The titles of certain essays by this the scientist, who was director of the Manufacture Royale des Gobelins, are enough to indicate the echo his researches found in the painter of the Windows, Circular Forms and Discs (1912–13): On the Law of Simultaneous Contrast of Colours (1839), Dissertation on the Vision of Material Colours in a Rotating Motion and the Numerical Speeds of Circles (1882).

Another aspect of the Ukrainian-Russian artist’s creative activity is that in 1916 he was working to assemble “various materials, colours and forms.” After his Symphony No. 1 in 1913 (MoMA), he continued to explore a new type of sculpture. From the mid-1910s to the 1930s, he created different types of sculpture. As for what he called in his 1925 “Memo” “counter-reliefs,” possibly under the influence of Tatlin, we are familiar with the Invalid Artist in the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum and the Toreador (private collection), which are probably from 1915. In 1933, his Polytechnic Sculpture (MNAM) provoked the sarcasm of the French press, which waxed ironic over these coils of metal, glass and wood. This construction has the rigour of the first spatial works made by the Soviet constructivists from 1921 onwards, but with a “baroque” inflection (the twists, the serpentine spirals which are the mark of the artist’s belonging to the Ukrainian School of the twentieth century).

It was in Odessa that the young Baranoff first learned his trade. One of his fellow students was none other than Natan Altman, whom he would meet again in Paris between 1910 and 1914, and then in Petrograd after the revolutions of 1917. When he finished his secondary education in 1905, he systematically devoted himself to his profession as a painter at the Academy of Saint Petersburg. By 1907, Baranoff–Rossiné’s innate eclecticism was already apparent. This word should not be taken as pejorative! Everything about the artist’s oeuvre points to his total originality, his “touch.” Like a bee, he took pollen from everything that came his way and pleased him, and turned it into honey. Between 1905 and 1907, the “World of Art” (Mir iskusstva) held sway in Russia. This secessionist movement led by Diaghilev and Alexander Benois recalled that art had no utilitarian function other than to serve Beauty.

The exhibition of Russian art organised by Diaghilev and Benois in Paris in 1906 saw poetic realism, art nouveau, symbolism and impressionism coexist peacefully under the banner of the “World of Art.” Traces of all these styles can be found in Baranoff’s landscapes, genre scenes, still lifes, and nudes from this period, but his dominant style is impressionism, which he modulated in multiple variations. Sometimes he created luminist effects with the play of light and shade, in the wake of Repin, the greatest painter of the realist school of Wanderers who, despite his aversion to “foreign discoveries,” had integrated, but without excess, certain principles of French impressionism (pleinairism, division of strokes, solar lighting, etc.); sometimes the heritage of Van Gogh was translated into somewhat coarse variations on the vibrations of pictorial space, doubled by a curious convergence with the first impressionist works of Malevich; sometimes the parcelling out of the canvas into small, nervously adjusted strokes was combined with the use of thick impasto creating a relief, as in the impressionist works of Kandinsky of the 1900s; and sometimes, too, the space was measured out by a network of small quadrilaterals (Self-portrait with a Brush, 1907 and other portraits from this period), or by small meshes, small parcels with which Vladimir Burliuk, his compatriot from Kherson, was constructing his canvases at the time of the first exhibition of what would later be misnamed the “Russian avant-garde” and should be called “Left-wing art in the Russian Empire and the USSR.” The young Ukrainian Baranoff himself took part in this important show, “Στέφανος,” held in Moscow in 1907. This name “Stephanos,” was taken from the title of a collection of poems by the Symbolist theorist Valery Bryusov, which referred to a wreath of flowers, in this case a garland of poems. The Russian name for this was “Venok” and in 1909 there was another exhibition in St. Petersburg called “Venok-Stephanos,” where Baranoff again showed his work. Together with his participation in the 1908 street exhibition in Kiev of work by the young painters of the future avant-garde (“Zveno”/”The Link”), this constituted his contribution to the new painting in Russia before his departure for Paris in 1910. In Russia at the time this was called “impressionism” in opposition to naturalistic realism or academicism, because other names had yet to be found, as they would after 1910: “futurism,” “futuraslavia” (budietliantsvo), or even “cubo-futurism.”

Arriving in Paris in 1910, the painter took the pseudonym of Daniel Rossiné, and that was how he signed his works until 1917. The French capital was in a ferment of experimentation. Matisse’s Fauvism was already being challenged by the cubism of Picasso, Braque and Léger, whose followers caused a sensation at the Salon d’Automne in 1911. Several of Rossiné’s compatriots, who had come from the Ukraine like him, including Alexander Archipenko, Alexandra Exter, Sonia Delaunay, Baroness Elena Frantsevna of Oettingen and her cousin Serge Férat (Yastrebtsov), who was the editor of the Soirées de Paris in 1913, were actively involved in the general movement of the arts to break away from the age-old figuration that had been limited to the mimetic reproduction of nature.

For many of these innovators, Cézanne was the main inspiration for the new Parisian style. The Master of Aix’s famous words about treating nature by “the cylinder, the sphere, the cone” was taken literally by the artists of the avant-garde. Rossiné painted a large number of canvases in the cubist style but, as always with him, he applied Cézanne’s precept with great flexibility, never sticking to a “pictorial recipe” but mixing highly diverse approaches as his inspiration dictated, going close for example to the pre-cubists (Village, The House by the Lake, Cock, 1911), to Gleizes (Nude Woman,The Forge, at the MNAM), or even to André Lhote with his rhythmisation of space by the play of fan-shaped curves. But he also asserted his personality intact by his flattening of objects, which would influence the style of David Shterenberg, who exhibited with him in Paris in 1914 and who, in the early days of the 1917 revolution, was the People’s Commissar for Arts (IZO). Also very much his own was his range of colours, with a dominant Fauvist tone but also a specific Slav inflection (harmonies of blues-reds-yellows-greens, as in Still Life with Chair).

From 1910 to 1914 Rossiné exhibited regularly at the Salon des Indépendants. With Sister of the Artist. Motherhood, shown at the Salon d’Automne in 1913 and noted by the poet and critic André Salmon, the painter added to his cubist volumes the futurist dynamism and orphist simultaneism of Robert and Sonia Delaunay.

At the same time, he painted a whole series of large-format paintings on biblical subjects (Apocalypse, Man on his Knees, Adam and Eve, etc.) whose symbolist iconography, including references to Michelangelo and William Blake, among others, was quite unusual, but whose workmanship took into account modern experiments with the possibilities of colour. The representation of the solar disc with its emanations in concentric circles shows convergences with certain works by Kupka and especially with the “simultaneous solar discs” of Robert and Sonia Delaunay. Rossiné’s correspondence with the latter indicates their shared artistic purpose.

The Delaunays’ friend, the Armenian Georgy Yakulov, one of the participants in “Στέφανος” in 1907, had been carrying out research on the solar prism since 1905, independently of Chevreul’s work. And he confronted his experiments with those of the Delaunay couple throughout the summer of 1913 at Louveciennes.

Rossiné, too, had been working in this experimental direction. In around 1910 he had made a palette, called “polychrome,” on which a series of colours were painted. At his solo exhibition in Kristiana, in 1916, he hung up a palette showing his colours and in an interview responded as follows to the Norwegian critics who were taken aback by his work:

“Have you seen my palette and […] on the palette you can get any shade you want. This is the law of contrasts between colours […]. White, black, red, any colour is transformed according to the one you place next to it. If you know colours, you cannot fail to see these changes. As you can see, I have divided my palette into sectors of different colours: green, blue, violet, red, orange, black, brown and white. So I can get exactly the shade I want.”[4] Today, the invention of the “polychrome” palette, which is the first of a whole series of inventions by Baranoff–Rossiné, may not seem so bold, but at the time it was really new. Several artists used it to advantage. On 10 December 1917, Natan Altman wrote from Petrograd:

“I find that Rossiné’s ‘polychrome’ palette 1) organises the work well; 2) helps to find an intense colour, 3) encourages one to treat the material with care and love. This palette is very practical to work with. I have been using it since 1911.”

We know that in around 1912 Daniel Rossiné was working in the field of music and colour. Here is what Kandinsky wrote to the Russian composer Thomas von Hartmann [Foma Aleksandrovich Gartman]:

“Rossiné (a young Russian painter), who is working on the theory of painting and especially of musical scores, is dying to meet you. He himself is fantastic. He may come to Munich again in September, otherwise he asks you to come to Switzerland (to Weggis near Lucerne – there is a centre for Swiss who paint: the Moderner Bund).”[5]

This is confirmed by Hans Arp in the memoirs he wrote in the 1950s:

“The Russian painter Rossiné, who visited me during this time (in Switzerland), was unexpectedly understanding of my attempts. Rossiné showed me some of his drawings, on which he described his inner world in a new way with coloured punctuation marks and lines. His and my works were concrete art.”[6]

Around 1914, Rossiné did more than make an original contribution to the cubist geometrisation of form, to futurist dynamism and to Parisian colourist experiments; he also created an iconography with fragments of ribbons with cylindrical volumes that curled in the space of the painting, unwinding and turning over in constant movement. This transposed the principle of the ribbon defined by the German mathematician Möbius into plastic space, as Max Bill would also do some thirty years later.

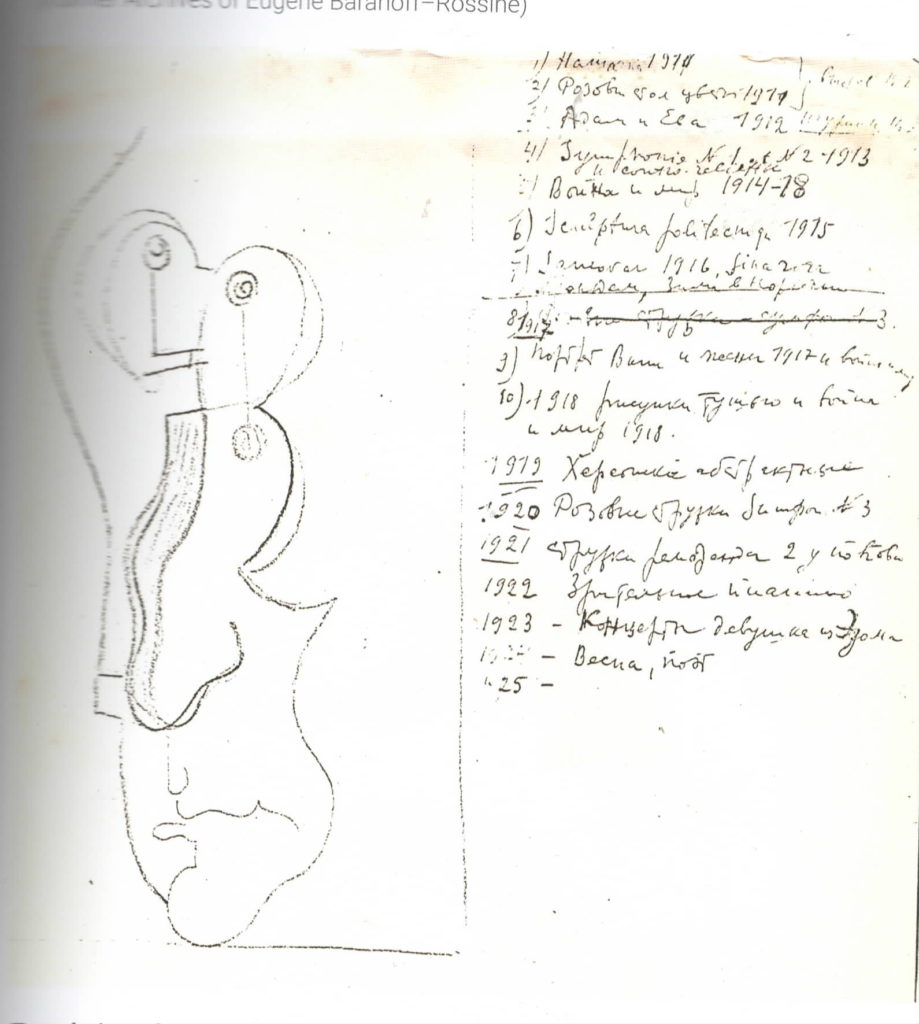

This led to a series of paintings entitled “Shavings” (Copeaux) in around 1919–20. Baranoff–Rossiné’s famous painting with this title, now at the MNAM, is not from 1910 as the date on the canvas, which has obviously been scraped at, seems to indicate. According to the “Memo” that the artist wrote in 1925 about his main artistic works since 1911, the piece is indeed from the abstract period in Kherson around 1919–20. I have translated this Memo, in which the Ukrainian painter sometimes mixes Latin and Cyrillic characters. Attempts to date Baranoff–Rossiné’s abstract creation to before 1914 are not justified and many works from the 1920s and 30s are wrongly dated to the 1910s.

These years of research were marked by two exceptional moments: the exhibition of two sculptures called Symphony at the 1913 and 1914 Salons des Indépendants and the destruction of one of these works, Symphony No. 2, which, according to Sonia Delaunay’s recollections, was thrown into the Seine after the 1914 Salon. This last action, which was part of a ceremony involving other painters, anticipates similar gestures, such as the ones carried out several decades later by Yves Klein. This exemplifies what, at that time, a form of behaviour typical of Futurism, and in particular of Russian Futurism. In one of their 1913 manifestos, the poets Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh wrote:

“To be torn up after reading!”

This was what one might call a pre-Dadaist spirit, like the conceptual acts of Marcel Duchamp. Moreover, the preserved Symphony No. 2, now at MoMA, shows how disconcerting these constructions of heterogeneous elements could be. Critics at the time spoke of “paradoxical assemblages of varnished zinc daubed with fresh and vivid colours, serving as a support for strange pepper mills, blue, cream or madder discs intermingled with unexpected springs and steel rods.” These objects are at the limit between painting and sculpture, narrowing the margin that separates pictorial art from sculptural art, as was then beginning to be practiced (Picasso’s first reliefs, Archipenko’s sculpture-paintings and Tatlin’s pictorial reliefs). It was no longer traditional sculpture that served as a structure, but the pictorial that was appropriating space, integrating what Margit Rowell called in a memorable 1978 exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York “the planar dimension”: this was the pictorial dimension unfolding in space, which the Soviet constructivists would systematise from 1920 onwards.

A dominant feature of Rossiné’s entire pictorial output after 1910 is precisely its sculptural potential. This is certainly one of the lines developed by cubism in its contrasting volumes, the other line being, conversely, the flattening of the elements structuring the pictorial surface, which would be raised to its maximum intensity in Malevich’s suprematism. In Rossiné’s work, this tendency towards volume is combined with a very particular way of making the subject of the representation stand out on the flat pictorial surface, thus contrasting the background of the painting with the object set against it. In most of the artist’s paintings between 1910 and 1943, the object is no longer integrated into the pictorial construction, but is like an excrescence whose contours, although anchored to the support of the painting, are clearly delimited in relation to the surface. There is never any pulverisation (raspyliéniyé) of the object, as Nikolai Berdyaev put it in his 1914 article on Picasso, but, on the contrary, its emergence, the concretisation of its voluminal mass.

For all his many activities, painting would remain the Ukrainian artist’s privileged domain until the end. If he made forays into other fields, the starting point was always his passion for the art of painting. After the outbreak of the First World War, he settled in the capital of Norway, Kristiana, and stayed there until the revolution of 1917. There he held the only solo exhibition of his career. Familiarity with Scandinavian expressionism, especially Edward Munch, and with Norwegian landscapes, resulted in a more muted palette and more pronounced line, and he even showed a neo-primitivist tendency to simplify the lines dominated by the concentric rays of the sun. But when he returned to revolutionary Russia, he created cubo-futuristic canvases with flamboyant colours and swirling spiral forms on the Norwegian theme, referring to the Möbius strip.

During the Russian revolutionary events of 1917, Rossiné returned to his country and played an active part in the reorganisation of the arts that was under way there. This was when he took the name we know him by today, Vladimir Baranoff–Rossiné. He showed his works in numerous group exhibitions and, like all artists, took part in agit-prop, decorating the Square of the Apparition of the Mother of God (Znamienskaya plochtchad’) in Petrograd in 1918, opposite the Moscow Railway Station, which became the Square of the Insurrection (Plochtchad’ Vosstaniya). He opened a studio in the rooms of the former Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts, which had become “Free Studios” (Svomas), and taught in the Higher Art and Technical Studios (Vkhutemas) in Moscow in the “Forms-Colours” section. It was then that the result of his simultaneist–synesthetic research took shape with the creation of his famous Optophonic Piano, which he demonstrated in 1924, on the eve of his departure for the West, at the Meyerhold Theatre, then at the Bolshoi in Moscow. The posters announced: “For the first time in the world: A colour–visual (optophonic) concert. The reincarnation of music in visual images with the visual piano invented by the painter Vladimir Davydovich Baranoff–Rossiné”;

or:

“Optophonic, coloro-visual concert: reproduction of music in colour with the help of a new invention, the visual piano of the painter Vladimir Davydovich Baranoff-Rossiné.”

At the Bolshoi, the performance was preceded by an introductory lecture by the literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky, who belonged to the “School of Form.” An orchestra, dancers and opera singers took part in the performance. The artist’s wife, Pauline Sémionovna Boukharova, was at the “piano.”

With the Optophonic Piano, Baranoff–Rossiné wanted, starting from the pictorial, to make real the romantic (especially German) and symbolist dream of the synthesis of the arts, what Richard Wagner had called the Gesamtkunstwerk. This notion had become almost magical by the beginning of the twentieth century; it was translated above all into the performing arts and, since then, theatre has always sought to be a “total art.” It has to be said that in order to clear up the ambiguities surrounding the word Gesamtkunstwerk, which were compounded by the monumental 1983 exhibition “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk” (The Tendency Towards the Total Art Work) in Zurich in its confusing of synthesist research with the search for totality. It is important to say that the Gesamtkunstwerk is defined as a work, an object, which unites sound, movement, form, colour and even smell in a concrete (and not fantastical or poetic) whole. The Optophonic Piano is part of a whole series of attempts to “combine the perceptions of our senses so that we experience the integration of simultaneous sensations, modified in time in keeping with a concerted rhythm, a particular artistic impression,” as Baranoff–Rossiné says in handwritten notes in which he recalls that the philosopher Eckartshausen had transcribed popular songs into a colour composition in the seventeenth century. He also mentions Johann Sebastian Bach’s childhood dream of a building in which architectural rhythms were combined with sound rhythms, where rainbows were transformed into perfumes, where the chromatic scale fell in bas-reliefs on the columns. Although this anecdote is apocryphal, it provides a good definition of the “Gesamtkunstwerk tendency.” The painter also refers to the eighteenth-century French Jesuit mathematician Castel, who derived the idea of colour scales from Newton’s optical theories; Abbé Castel published his book La musique en couleurs in 1720 and invented an “Ocular Harpsichord” (the composer Telemann translated the description of this harpsichord into German in 1739). Numerous attempts were made at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth – we need only think of the Remington Colour Organ (London, 1895), of Scriabin’s “keyboard with lights” (Tastiera per luce, Moscow, 1911), of Arnold Schönberg’s colour scheme for his choral work Die glückliche Hand (1911), of the Danish singer Thomas Wilfrid’s Clavilux (New York, 1922), or of the “chromophonic” instrument of the French composer Carol-Bérard, who presented his ideas in La Revue musicale in 1922. Baranoff–Rossiné systematised the experiments of his predecessors, who were mainly scientists or musicians (Schönberg, who was both a composer and a painter, is the exception). He wanted to “extract the elements of music (intensity of sound, pitch, rhythm and movement) in order to bring them closer to similar elements that exist or can exist in light.” At the Second Congress of Aesthetics in Berlin in 1925, the Optophonic Piano captured attention. Its abstract dynamic paintings (coloured discs whose movement depended on the keys of the keyboard) created moving images that were projected onto a screen in time with the music. They show that the cinematograph, then still in its infancy, had given the painter pointers for solving the problem of the relationship between movement/light/music; but at the same time they were part of the technological research that sought to improve the cinematographic art itself. As Baranoff–Rossiné wrote,

“Art can at last breathe freely and allow itself to make a gift to Nature, the cinema in colour, while preserving the elements of pure art.”

With optophony, the Ukrainian painter intended to create a new artistic genre:

“It is not a matter of simply superimposing one phenomenon on another,” he wrote. “By integrating the sensations of different nerves we should come to experience a new artistic impression.”

Although we can now see applications of these intuitions in kinetic art in general, in the cinema, and even in pop music (light shows), the painter was never able to fully realise his dream of creating a “European optophonic centre.”

After the “polychrome” palette, after the optophonic piano, Baranoff–Rossiné made other inventions: the “photo-chromo-meter” or “mensurator” which was “a complete and perfected magnifying glass” to determine mathematically the five[mais on ne cite que quatre] qualities of a precious stone (weight, size, impeccability, vivacity); the “Chameleon” or “Pointillist Camouflage” process is an astonishing application of pictorial art to military art, since it involves projecting spots of colour magnified to the maximum on any kind of military target, “so that it looks like the air.”

All these para-pictorial inventions, to which can be added one that has nothing to do with painting, the purely commercial “Multi-Perco,” a “patented apparatus for the manufacture, sterilisation and distribution of various carbonated drinks (Vitaminade, Expressinade, wines, ciders, aperitifs, etc.),” can be explained by the general situation of artists, and in particular artists from the Russian Empire and the USSR, in France during the interwar years. As André Warnod wrote in 1925, “The Russian painters of Montparnasse, who cannot live by their painting alone, provided for their material needs by doing other jobs. They accept all sorts of tasks. Some are taxi drivers, window cleaners, but most are decorators, batik workers, stencillers, etc., or even house painters. They make art outside of their working day.”

In the 1920s, Baranoff–Rossiné’s friend Sonia Delaunay, who like him was originally from Ukraine, turned her Paris flat into a workshop offering “dresses, coats, scarves, carpet bags, simultaneous fabrics,” thus putting the most modern discoveries in pictorial art at the service of sartorial art. Baranoff–Rossiné, for his part, composed a letterhead which offered: “Inventions. Studies. Scientific, optical and electrical research, mechanical improvements. Construction and development etc..”

Of course, this was just another way of earning a living, without straying too far from the field of painting, but for Baranoff–Rossiné there was above all a compelling need to constantly find new forms and ideas. This industrious innate genius was expressed in his pictorial creation after 1925 by very different stylistic phases (surrealist post-cubism, abstraction based on the biomorphic forms of Hans Arp, with whom he had been in contact since the beginning of the 1910s,[7] and then the organic and inorganic world), but what dominates is the undulating, melodic, dynamic, enveloping line, which imparts a musical rhythm to his paintings. This undoubtedly explains the invitation extended to Baranoff–Rossiné by the founder of musicalism, Henry Valensi,[8] to exhibit his works at the exhibition of artists working in this trend in Limoges in 1939.

Baranoff–Rossiné was a painter of brilliant intuitions and many of his works contain discoveries that would be further developed later on. However, his psychic complexion kept his mind in constant turmoil, did not allow him to rest, and pushed him to explore ever new terrae incognitae, and this prevented him from fully pursuing individual discoveries, leading him to abandon them in order to make new ones. There is something in this Ukrainian artist of the fantastical Khlestakov, a character in his compatriot Gogol’s The Government Inspector, but, unlike the latter, he did not confine himself to the invention of seductive and alluring chimeras. His abundant, multifaceted work enriches the art of the twentieth century with its own original sound, occupying a privileged position in the “left-wing art in the Russian Empire and the USSR” that was the exemplary crucible of the essential artistic revolutions on which the art of today still lives, unable as it is to throw off this prestigious and difficult-to-surpass heritage.

Jean-Claude Marcadé

Baranoff–Rossiné’s “Memo” in 1925 (Former Archives of Eugène Baranoff–Rossiné)

Translation of the “Memo

1) [illegible] 1911

2) Pink table flowers 1911- expo. 1912

3) Adam and Eve 1912 Shurik and [illegible]

4) Symphonies N°1 and N°2 1913 and counter-reliefs

5) War and peace 1914–18

6) Sculptura politecniqa [sic] 1915

7) Samovar, Synagogue, Trondheim, Winter in Norway

8) [crossed out]

9) Portrait of Vanya and my wife

1917 and war and peace

10) 1918 Indian ink drawings and War and Peace 1918

1919 Kherson Abstractions

1920 Pink shavings. Symphony N°3

1921 Shavings [illegible].

1922 Visual piano [sic]

1923 Concerts, the young line of Edom

1924 Spring, the poet

and 25 –

[1] According to the Catalogue des œuvres de Baranoff–Rossiné by Christiane Wiehn, established as a dissertation presented at the École du Louvre under the supervision of Michel Hoog in 1976.

[2] Here we see that Rossiné presents himself as coming from “Little Russia” (one of the names for Ukraine in the Russian Empire at the time) and travelling in “Great Russia” (one of the names of Russia at the time).

[3] Former Archives of Eugène Baranoff–Rossiné.

[4] “Vandreren Mr.Rossiné ug hans Palet” [The migrant Mr.Rossiné and his palette], Tidens Tegen, 19/11/1916.

[5] Letter from V.V. Kandinsky to F.A. Gartman of 20.VIII. 1912, Russian National Archive (RGALI), Moscow

[6] Hans Arp, Unsrem täglichen Traum, Zurich, 1955, p. 8: “Der russische Maler Rossiné, der mich in dieser Zeit besuchte [in der Schweiz], brachte dagegen meinen Versuchen ein unerwartet grosses Verständnis entgegen. Rossiné zeigte mir einige seiner Zeichnungen, auf denen er mit farbigen Punkten und Kurven seine innere Welt auf eine nie gesehene Art dargestellt hatte. Seine und meine Arbeiten waren konkrete Kunst.”

[7] See the memoirs of Hans Arp,Ibidem

[8] On this painter, see the catalogue Henry Valensi. Du Futurisme au Musicalisme, Paris, Galerie Le Minotaure, 2014.