-

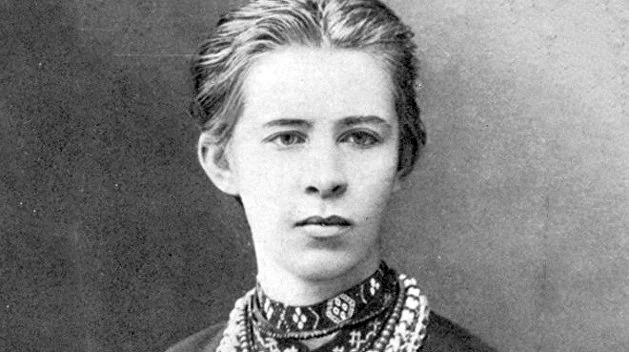

La jeune Ukrainienne Sonia Stern-Terk à Saint-Pétersbourg, en Allemagne, à Paris avant 1910

La jeune Ukrainienne Sonia Stern-Terk à Saint-Pétersbourg, en Allemagne, à Paris avant 1910 „Was der Mensch in seiner Kindheit aus der Luft der Zeit in sein Blut genommen hat, bleibt unausscheidbar“ Stefan Zweig, Die Welt von Gestern, [1944][1] Sur la jeunesse pétersbourgeoise de la future Sonia Delaunay, avant son départ pour l’Allemagne le 21…