ANNEXE EN ANGLAIS DE 1918 DE LA MONOGRAPHIE “MALÉVITCH ” (PARIS-KIEV, 1912) : “FEMALE TORSO No. 1” BY MALEVICH IS THE IMAGE OF THE NEW SUPREMATIVE ICONICITY

Jean-Claude Marcadé

“FEMALE TORSO No. 1” BY MALEVICH IS THE IMAGE OF THE NEW SUPREMATIVE ICONICITY

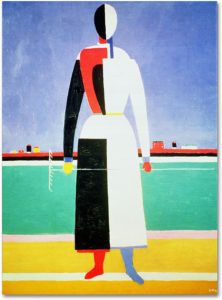

The painting “Female Torso No. 1” (oil on wood, 41 x 31 cm), which appeared in a private collection in Kyiv, brings new light to one rather mysterious series of the late 1920s, which was shown in a retrospective exhibition of Malevich in Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow) in 1929 and in the Art Gallery (Kyiv) in 1930. It is still difficult to classify the artist’s paintings after 1927. “Female Torso No. 1” allows us to bring in some order to this important part of the paintings of the Ukrainian artist.

BACKGROUND

Between 1928 and 1934, the founder of Suprematism intensively returns to painting and creates more than two hundred works, the exact chronology of which cannot be established today. We only know that for a retrospective exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery in 1929 and at the Art Gallery in 1930 in Kyiv, Malevich draws a series of impressionist paintings which he dates by the beginning of the 20th century and depicts the peasant themes of 1912-1913 in a new way, which he also antidates.

The artist then reinterprets his early cubofuturism, leaving the old dating. He dates works made in the late 1920s by the pictorial culture that they represent, and not by the date of their drawing. Thus, “Female Torso No. 1” is dated as of 1910, and we will return again to this problem. The entire series of the works (“The Mower” at the Tretyakov Gallery, “At the Cottage”, “Van’ka Boy” at the State Russian Museum, etc.) employs again the early cubofuturistic elements in order to bring them into a structure that takes into account the achievement of Suprematism.

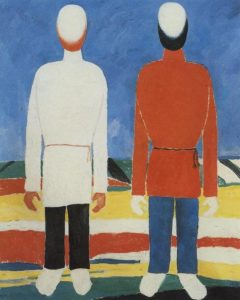

So, this structure is built of colorful stripes for the background and simplified planes for the body of the characters (see “Girls in the field” at the State Russian Museum[1]). The invariant verticality of those characters who, like in the church icon, occupy the central space of the picture is noted. In post-suprematism, a person stands in front of a universe whose color rhythms pass through him/her. The horizon line is low. There is no real color simulation.

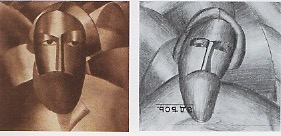

THE MEANING OF ICON PAINTING

Malevich’s return to the image after 1927 is actually a synthesis in which objectivity pierces people depicted in the position of eternity. Between 1909 and 1913, the face of the painter Ivan Klyun served as the plot of various stylistic metamorphoses, symbolist, primitivist, geometric, cubofuturistic, realistically abstruse. After 1927, it became the paradigmatic face of the peasant, adopting the basic structure of the prototypes of icon painting, in particular the Pantocrator or the Miraculous Savior[2].

This borrowing of the basic system of some icons is not, as in Boychukism, a “juggling of centuries” [“tricherie avec les siècles”] as Apollinaire[3] puts it, but a modern application of icon painting as a “form of the highest culture of peasant art”[4]:

“Through icon painting, I understood the emotional art of the peasants, which I loved before, but did not understand the whole meaning that was discovered after studying the icons.”[5]

POSITION IN THIS CONTEXT OF THE PICTURE “WOMEN’S TORSO No. 1”

The four main elements are of great interest in this work: its iconicity, its popular primitivism, its alogism, and its energy of color.

SUPREMATIC ICONICITY

The painting “Female Torso No. 1” is painted on a linden board. Its background consists of oil paint, to which animal glue and chalk are mixed. Linden wood is one of the noble materials used by icon painters in Russia and in the Balkans; glue and chalk are an integral part of gesso, with which artists cover the board before they integrate the drawing into the plot. This drawing is called the sketch, it draws the outline of the plot before applying paints.

In the painting “Female Torso No. 1”, it is clear that Malevich returns to the principle of the icon-picture, which he initiated in the early 1910s, but here he applies a new structure. Of course, Malevich is not an icon painter, he is a painter who wanted to give the easel picture the same structural and metaphysical setting as the church icon in order to develop a new image of the universe. In this, we repeat, it differs from the Byzantine Boychukist school, which strove to garment modern reality in the forms of traditional icon painting.

On the formal side, you can consider “Female Torso No. 1” as a suprematization of the icon. He is the prototype of a series of paintings and drawings between 1928 and 1932.

The works that immediately followed this prototype are known: the canvas “Torso. The First Formation of a New Image 1928-1929” in the Tretyakov Gallery, on the back of which is written by Malevich’s hand: “No. 3 The First Formation of a New Image. The Problem is Color and Form and Content,”[6]

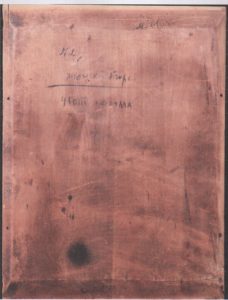

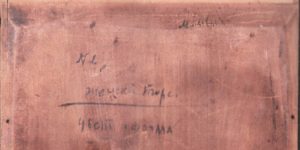

and on the back of our painting “Female Torso No. 1”, Malevich wrote: “No. 1 Female Torso color and shape“

; another “Female Torso 1928-1929” is also known, which is also in the State Russian Museum, oil on plywood, on the back of which the artist writes with his own hand: “No. 4 female torso – Development of the 1918 motive.”

My hypothesis is that another canvas of the same late 1920s, located in the State Russian Museum, which has an identical structure as our “Female Torso No. 1”, namely, “Torso (figure with a pink face) 1928-1929”[8]

is actually number 2 which immediately follows number 1 (our “Female Torso”) and precedes number 3.

That is, Malevich used “Female Torso No. 1” as a prototype from which he created variations in the likeness of a composite of paints and shapes. This hypothesis seems to me confirmed by the presence of two holes on both sides of the board, indicating that it was nailed to serve as a model for further work.

Let us go back to the “Female Torso No. 4”

, since here we are talking about a new step in developing the “new image”: the female face has an eye and a mouth, but also without the slightest realism (for example, there is no direct image of the nose); the suprematic iconic timeless character of the image is fully marked.

DATING

We find, as in our painting “Female Torso No. 1”, dating of 1910 in the works which, most likely, follow from this prototype. To understand what the Ukrainian artist is implying, one should recall his letter to L. M. Lisitzky dated February 11, 1925, at the time when he was attacked by the adherents of Marxism-Leninism and he was accused of idealism and mysticism. He not only does not give up his thoughts, but also reinforces them with his highly metaphorical-metonymic style, Gogol’s biting humor. Speaking about his heads of the “Orthodox peasants” of the early 1910s, he announces:

“It turned out, I painted the ordinary head of a peasant that it is unusual, and really if you look from the point of view of the East, then it’s everything that is ordinary for Westerners, then for people of the East it becomes unusual, everything ordinary turns to the Icon, for the East is iconic and it is, and the West is a machine, an object, a toilet, utilitarianism, technology, and here is a plant and factories, this is a new hell from which People will be freed through a new image, that is, through a new Savior. I painted this Savior in 1909-1910, he became a savior through the Revolution, the Revolution is only a banner, the thesis through which he became a synthesis, that is, the “New Savior” […]

I did not go “past the Revolution” – on the contrary, I foresaw its synthesis back in 1909-1910 in the New Savior. And this is now becoming the main thing. The Tatlin Tower is a fiction of Western technology, he will now send it to the Paris exhibition, and of course he can also build a reinforced concrete urinal so that everyone can find a corner. It’s so clear to me that without a lamp I can write (paint) about the West and the East. “[9]

So it is natural that Malevich, when he returns to easel painting and seeks to convey “in color and form”, as it is written in our “Female Torso No. 1”, a new image-icon of a man and the world, continues his poetics of the beginning of 1910 when the image of the peasant (not in the sociological sense of the word, but in the sense of a man in the lap of nature) is revealed in the prism of the image of the Orthodox.

In this section, we find the same iconic features in the late 1920s in the painting “Suprematism in the contour of a peasant woman” [“Woman with a rake“] from the Tretyakov Gallery

or in “Girls in the field”

and “Suprematism in the contour of athletes” from the State Russian Museum[10],

which are in the spirit of our “Female Torso No. 1”, which affirms the purely pictorial framework of the artist.

Malevich could say that he does not portray the faces of many of his characters because he does not see the person of the future, or most likely because the future is an unknown mystery.

Christological references are present in many images of post-Suprematist creativity, often they are camouflaged.

Among the impulses that could lead the artist to these “faceless faces”, there is the Roman Catholic practice of worship (adoratio) before the wafer (guest) in a monstranza (ostensorium).

Despite the fact that Kazimir Severinovich, being baptized according to the Roman Catholic rite, was not a churchman, he in all probability visited churches in childhood and in his youth. In addition, we know from correspondence with M.O. Gershenzon in 1920 from Vitebsk that he “returned or entered the religious world”:

“I don’t know why this happened, I go to churches, look at the saints and the whole spiritual world”[11]

Could the artist, among the impulses from the “Religious World”, receive an impulse from worship in front of a guest who is in the hole of the Catholic Ostensarium. And there is “presence-absence.”

The ostensarium well is round or sickle-shaped. Just “faceless faces” have a lunar contour. The monstrance’s hole was traditionally surrounded by bronze, silver or gold artwork, often depicting the sun. But she could have been without this ornament. Namely Malevich wants to leave the Solar World, leaving only a contemplation of the Pure action.

It should be noted that Malevich refers to the adoration of the Blessed Sacrament in the Catholic Church in his astonishing text on Lenin “Extract from the book on the Objectlessness” (1924):

« Lenin was buried in a glass coffin for no other reason except that he should be seen as a Blessed Sacrament.This forecast that I wrote has really come true. When I wrote it I did not know about the idea of the glass slit. I had considered the idea of the glass coffin supposing that a man who has been sanctified is a Blessed Sacrament, and the degree of his holiness corresponds to the holy sacrament in the Catholic world in which the Sacrament is put under glass.”( Malevich III, The world as Non-Objectivity. Unpublished writings, 1922-25. (ed. Troels Andersen),Borgen, 1976, p. 315-36)

PRIMITIVISM

Malevich calls in this era for exposure, not for wild accumulation. This return to primary rhythms, to the minimalism of figurative expression, also deals with the poetics of folk art, which seeks visual efficiency with the help of sketchy drawings. Dmytro Gorbachov showed how these Malevich’s “faceless faces” resemble rag dolls created in the peasant Ukrainian world. It is interesting to note that since July 1930, two paintings of the peasant cycle were among the exhibits of the exhibition “Sowjetmalerei” (Soviet painting) in Berlin. They were dated 1913 and 1915! The critic Adolf Donat describes them as figurative paintings depicting characters resembling tight and faceless dolls in front of flat landscapes. He adds:

“That ‘colossus’ is visible, in which a person is displaced simultaneously in the arts and around them.”[12]

In the same way, the colored stripes that have the figure of the “Female Torso No. 1” next to them, are a kind of picturesque echo of those polychrome stripes on the aprons of the Ukrainian peasant women, like many handmade towels and carpets, especially in Polesie, where the Malevich’s family comes from. The artist even used these stripes in a lot of post-suprematic paintings and even they make up objectless (pointless) canvas painting of 1932 from the State Russian Museum[13]. These polychrome abstract stripes refer to aerial vision of the fields. This is the last statement of outer space, which protrudes through the contours of man and nature. Suprematism blew up any visible realistic outline, while post-Suprematism restores the visible outline of things, while preserving the demands of “peace as pointlessness.”

The theme of the windowless house also appears before Malevich’s prison and interrogations at the GPU from late September to early December 1930. Here, it seems, the matter is about a simplified minimalist primitivistic arrangement, almost graffiti, of the painter’s architectural thought, his “architectons” with its so complex form; like the character of “Female Torso No. 1”, with whom he adjoins, this house is another mystery of what will be the dwelling of a human being in the future. All houses depicted or painted in 1928-1930 have the same white color of Ukrainian huts. After 1930, this primitive house will become the emblem of a prison symbolized by the Red House from the State Russian Museum[14], in which a man of a totalitarian society is already imprisoned and where red expresses the suffering to which the prisoner is subjected.

In the same way, after being subjected to the interrogations by the KGB and spending time in prison, Malevich’s faceless characters become more and more representatives of suffering humanity; they seem to be connected, ugly. Nevertheless, the artist continues to adhere in parallel to the task that he expressed in “Women’s Torso No. 1,” namely, the further development of the purely pictorial problem of “color and form.” In this regard, he wrote on the back of the canvas of the 1930s “Two male figures” from the State Russian Museum:

“An engineer uses one or another material to express his purpose, the artist painter takes one form or another of nature to express color sensations. K. Malevich 1913 Kuntsevo.”[15]

It’s funny that Malevich tried to write his text using pre-revolutionary spelling, supplying the endings in the consonants with a solid sign! Of course, he gives, as usual in these cases, not the date the drawing was painted, but the initial date when this purely formal task was conceptually conceived.

ALOGISM

The character of the “new image” in the form in which it is found in “Female Torso No. 1” is very peculiar: in it, at the same time, the woman is represented facing us and facing the universe. It seems that the right white part (face and torso) appears to us full-face, while the left red-black side, which is raised, gives the impression that the character turned to us backwards and looks at the world.

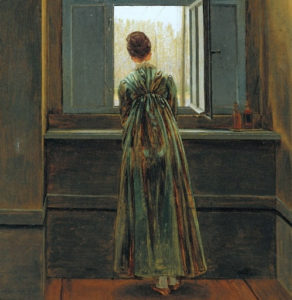

Another element, whether conscious or not for the artist, which may attract our curiosity, is an echo of the famous painting by Caspar David Friedrich, “The Monk by the Sea”, (1808-1810) from the Berlin National Gallery

This would mean that here the iconicity of Malevich’s work is coupled with the reference to the world art. Others paintings by Friedrich are even closer to “Female Torso No. 1” : “A Woman Before the Sunset” from the Folkwang Museum in Essen

or “Woman at a Window”

Une jeune femme se penche a la fenetre de l’atelier de Friedrich. C’est Caroline, l’epouse du peintre. Tournant le dos au spectateur, elle regarde couler l’Elbe. Les seuls signes de vie sont la femme, le vert delicat des peupliers, et le ciel de printemps. Dans ce travail, Friedrich a adopte un theme de predilection du romantisme, le cadre evoque un desir de l’inconnu. Le regard vers l’exterieur, contemplation de la nature, retour vers l’interieur de soi centre spirituel de l’individu.

See also “Traveler in Front of a Sea of Fog” from Kunsthalle in Hamburg.

The artist saw without a doubt the art of Friedrich when he was in Berlin in April-May 1927[16].

The alogism of the character’s representation in “Female Torso No. 1” can be found too in all three other paintings of this cycle: “Torso (Figure with a pink face) <No. 2>”, “Torso (Primary formation of a new image) No. 3” and “Female torso No. 4 ” We observe in all these paintings the same raised left shoulder, which turns its back on us. There is no depiction of hands that could be interpreted as a kind of disfigurement, as it will happen in the paintinge after 1930. In fact, one can imagine that the arms are crossed with a cross or tucked in the back or in the front. Moreover “Torso N° 3,(Primary formation of a new image), has one arm turned towards us and we can assume that on the left side which turned its back on us, the arm is folded down. And, moreover, it seems that Malevich wanted to dialogue, creating a new form, with the torsos of his compatriot Archipenko who, from 1914, created a whole series of truncated, armless female forms.

In No. 4 we note an even stronger alogism: on the left side we see the overlapping on the “shoulder” of elements that can indicate suprematist clothing with a collar. The contrast with the right-hand side turned towards us is very strong due to the bright presence of a white square on it on the shoulder, which is marked by a slight bend, while the beginning of the arm is represented.

The white veil surrounding the woman gives her the character of a Bride. Recall an article-poem in the Moscow newspaper Anarchy on June 12, 1918, “Engaged in a Horizon Ring,” which describes artists of all arts as lovers of the earth who seek its “hidden beauty”:[17]

“Beauty seekers walked across the face of the earth, among the rings of the horizon.”[18]

The earth appears as a “rich bride,”[19] to which “lovers engaged in a horizon ring aspire”[20].

COLOUR