Exposition Bernard Manciet à l’écomusée de Marquèze

By Jean-Claude on Juin 21st, 2024

Exposition Bernard Manciet à l’écomusée de Marquèze

Annada Manciet (seguida…)

À l’ Écomusée de Marquèze à Sabres

-

Le 16 mai : 18h30 – Rencontre au Pavillon #2

“L’Enterrement à Sabres : histoire d’une œuvre majeure du XXe siècle”

présenté par Guy Latry

-

Le 30 mai : 18h30 – Spectacle

Enterrement à Sabres

par La Compagnie “Du Parler Noir”

-

Le 13 juin : 18h30- Rencontre au Pavillon #3

Une promenade à deux voix dans l’oeuvre de Bernard Manciet

par Guy Latry & Isabelle Loubère

-

Le 20 juin – 18h30

Présentation du livre de Éric Audinet (éditions Confluences) et Bernard Marcadé (universitaire, collectionneur et traducteur) : présentation du livre sur l’œuvre picturale de Manciet.

-

Le 4 juillet : 18h30 – Spectacle

QUELQUES CIMAISES DE L’EXPOSITION

SUPRÉMATISME ET CONSTRUCTIVISME DANS L’EMPIRE RUSSE ET L’URSS (2017, revue Ligeia)

By Jean-Claude on Juin 17th, 2024

SUPRÉMATISME ET CONSTRUCTIVISME DANS L’EMPIRE RUSSE ET L’URSS

(2017, revue Ligeia)

Dans cet article je vais rassembler des recherches, des analyses, des réflexions que j’ai pu faire depuis quarante ans à différentes époques. Son propos est de distinguer deux mouvements essentiels de l’avant-garde européenne à l’orée du XXe siècle – le suprématisme et le constructivisme nés, l’un dans l’Empire Russe en 1913-1915, l’autre en URSS, en 1921-1922. Faire cette distinction est une nécessité non seulement d’ordre strictement historique (celui de l’histoire de l’art), mais encore plus d’ordre théorique, philosophique et conceptuel. Pourquoi faut-il encore aujourd’hui, cent ans après la naissance du suprématisme et du constructivisme, appeler à respecter ce qui nous a été légué par les oeuvres et les écrits, en particulier de leurs principaux fondateurs et coryphées, Malévitch et Rodtchenko? Parce qu’il faut constater que le constructivisme a de façon impérieuse pris le dessus tout au long du XXe siècle dans les différentes contrées européennes, faisant oublier que ce mouvement était né tout d’abord comme constructivisme soviétique, son nom apparaissant pour la première fois en 1921 avec un “Groupe de travail des constructivistes” à l’intérieur de l’Institut de la culture artistique (Inkhouk), groupe qui organise deux expositions pionnières à Moscou, celle de la “Société des jeunes artistes” (Obmokhou) en mai et, en septembre, celle intitulée “5×5 =25” (5 oeuvres de 5 artistes – Varst[Varvara Stépanova], Vesnine, Lioubov Popova, Rodtchenko, Alexandra Exter). Les catalogues de ces deux expositions ne portent pas encore la mention “constructiviste”, celle-ci apparaîtra explicitement, pour la première fois publiquement, en janvier 1922 lors de l’exposition moscovite “Constructivistes” qui présentait les sculptures des frères Guéorgui et Vladimir Stenberg et de Médounetski.[1]

Or, petit à petit, à cause de la parenté iconographique apparente des figures géométriques dans le suprématisme et le constructivisme, on en est venu à inclure Malévitch dans le constructivisme, ce qui doit le faire se retourner dans sa tombe!

À cela s’ajoute l’erreur qui a été celle du livre pionnier de Gérard Conio dans les deux tomes intitulés Constructivisme russe (Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1987). Dans cet ouvrage qui, par ailleurs, a joué et continue à jouer un rôle de premier plan par sa traduction et sa présentation en français de textes capitaux de l’art de gauche en Russie et URSS, l’auteur n’a pas indiqué que ce qui a précédé la naissance d’un mouvement autonome constructiviste en 1921-1922 était un stade pré-constructiviste. Bien que dans sa préface, il ait bien marqué ce qui distinguait un Malévitch et un Tatline, les titres des rubriques introduisant les traductions impliquent comme “constructivistes” des textes qui ne le sont pas, même s’ils annoncent le constructivisme de 1921, ou qui sont même contraires au constructivisme, tel le profond article de Malévitch “Sur la poésie” ou celui de Kandinsky “De la construction scénique” (ces articles se trouvaient dans l’unique numéro de la revue Iskousstvo [L’Art] de 1919 dont Gérard Conio a tenu à traduire l’intégralité).[2]

La confusion vient du fait que plusieurs artistes qui ont contribué à la gloire du constructivisme ont reçu des impulsions décisives du suprématisme malévitchien. C’est le cas des frères Pevsner et Gabo, cosignataires du fameux “Manifeste réaliste” placardé en 1920 au centre de Moscou, texte qui ne comporte pas le mot “constructiviste”, quoi qu’en ait eu Gabo qui a essayé de l’y introduire a posteriori.[3]C’est le cas aussi de Lissitzky, de Rodtchenko, de Lioubov Popova, de Klucis qui ont été dans l’orbite de Malévitch à leurs débuts.

Une autre confusion a été entretenue par l’exemple qu’a pu donner ce qui s’est appelé et continue à s’appeler le “Constructivisme polonais” qui englobe, à partir de 1924, autour d’un noyau constructiviste international, du moins au début, une veine nettement suprématiste, celle de Wladislaw Strzeminski, celle, surtout, de Katarzyna Kobro dont l’oeuvre construite est cent pour cent suprématiste. L’exposition pionnière de Ryszard Stanislawski et Andrzej Turowski au Musée Folkwang d’Essen et au Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller d’Otterlo en 1973 a consolidé cette confusion.[4]

L’historien de l’art suisse Antoine Baudin a été un des pionniers en langue française de la connaissance de l’avant-garde polonaise et tout particulièrement du “Constructivisme polonais” dont il analyse bien la situation dans un axe Moscou-Berlin : Moscou pour ses expositions, ses manifestes en 1921-1922, et Berlin, “centre de diffusion des principes du constructivisme russe à un moment crucial de son évolution”[5].

Strzeminski quitte Vitebsk pour la Lituanie dans la seconde moitié de 1922 et, cette même année, il publie ses “Notes sur l’art russe” où il critique de façon virulente Tatline et le tatlinisme, dont il affirme qu’il est “un appauvrissement du cubisme, le développement excessif d’un élément secondaire au détriment des autres”[6]. Son jugement est encore plus sévère à l’égard des constructivistes soviétiques et des productionnistes; pour lui, Rodtchenko et ses suiveurs “n’ont même pas idée des efforts qu’il a fallu pour aboutir aux solutions du cubisme et du suprématisme […], compilant dans leurs oeuvres des fragments de celles de leurs prédécesseurs”[7].

En revanche, il présente de façon positive le suprématisme qui est “la première explosion et, à ce jour [en 1922], la plus puissante de l’art constructif” et Malévitch “un artiste d’une dimension colossale, géant qui déterminera la destinée de l’art durant tout un siècle”[8]

Strzeminski est donc clair quand il distingue en cette année 1922 une ligne qui se veut héritière de Tatline, une ligne constructiviste-productionniste et la ligne suprématiste qui se réclame de Malévitch et dont, entre autres, Katarzyna Kobro est une représentante éminente.

En 1983, la grande exposition de Dominique Bozo et Ryszard Stanislawski au Centre Georges Pompidou “Présences polonaises. Witkiewicz. Constructivisme. Les contemporains” ont conforté ce brand qu’est devenu le mot “constructivisme”. Andrzej Turowski indique bien les deux pôles du Constructivisme polonais qui se forma comme groupe sous cette appellation en 1924. D’un côté, l’utilitarisme de Mieczyslav Szczuka en harmonie avec les données socio-politiques et, de l’autre, la quête des structures qui rythment le monde dans son essence chez Strzeminski qui veut aller au-delà du suprématisme de Malévitch.[9]

Cela a malheureusement renforcé, une nouvelle fois, la confusion qui a régné dans la critique occidentale. J’ai, à plusieurs reprises, soulevé cette question fondamentale. J’ai essayé de faire disparaître cette confusion dans mon Avant-garde russe. 1907-1927 (Paris, Flammarion, 1995, 2007) en consacrant deux chapitres – l’un au “Pré-constructivisme” (1913-1920, p. 239-267), l’autre au “Constructivisme” (p. 269-323). [10]

Dès 1977, je déclarais :

“Faut-il encore rappeler que des formes géométriques sur un tableau ne permettent pas de le déclarer automatiquement „constructiviste”. Le constructivisme est un mouvement bien précis, né en Russie, dont le nom même ainsi que la théorie n’apparaît pas avant 1920. Parler sans précaution de constructivisme avant cette date est un abus flagrant de vocabulaire, autorisant les amalgames les plus confus; en fait, le constructivisme russe a mis dans sa théorie l’accent sur le problème de la construction dans la mise en forme d’une oeuvre d’art, en associant ce principe à une philosophie générale de la vie à dominante matérialiste. Il est certain que la théorie et le mouvement constructivistes sont nés d’une pratique bien antérieure à 1920, de la mise en forme, de la construction, de la facture-texture d’un objet artistique, inaugurée en Occident par le Cubisme et le Futurisme; poursuivie en Russie par le Cubofuturisme, le Rayonnisme, le Suprématisme, les contre-reliefs de Tatline et les recherches d’un espace scénique „construit” chez Malévitch (La Victoire sur le Soleil, 1913), Alexandra Exter (Thamira le Citharède, 1916 et Salomé, 1917) ou Georges Yakoulov (arrangement du Café Pittoresque, 1917). Comme tous les mouvements, venant après d’autres courants, le Constructivisme russe a privilégié et isolé dans les esthétiques précédentes un certain nombre de principes qu’il a poussés à leurs conséquences extrêmes en en faisant un système parfaitement original. Si le Constructivisme a utilisé, entre autres, le suprématisme, il n’en a retenu que „les plumes de l’organisme”, selon l’expression de Malévitch,[11] farouchement opposé à la culture du matériau, au productionnisme et au constructivisme.”[12]

En 1995, je notais :

“Bien qu’il se soit quelque peu dégrisé, le discours sur le constructivisme reste très inflationniste. Voilà un des mots, qui, presque comme „avant-garde”, a des vertus mythologiques pour un public toujours à l’affût, à la fin du XXe siècle, de succédanés au réel. Depuis deux décennies déjà je profite de chaque occasion qui m’est donnée pour dénoncer l’emploi abusif du mot constructivisme , du moins pour ce qui est de l’art russe dans le milieu duquel, si je ne m’abuse, ce mot a été forgé pour la première fois, c’est-à-dire en 1921.”[13]

Donc, en effet, la frontière a pu paraître fragile, mais, pour autant, elle ne permet pas d’assimiler les deux mouvements qui dominent les fameuses “Années 1920”, ou, pire, d’inclure le suprématisme dans le constructivisme. Cela a pu arriver dans les accrochages du MNAM. Malgré mes précédentes interventions écrites et verbales, j’ai pu voir dès 2015 (et j’ai constaté cela en encore au début de 2017) une salle intitulée “Constructivismes”. Dans cette salle, son cartel introductif et ses commentaires ne faisaient pas connaître aux visiteurs que les deux mouvements principaux de l’art de gauche soviétique sont le suprématisme, né en 1913-1915 et le constructivisme, né en 1921-1922.

Voici le texte intégral de la notice qui introduit cette salle où sont exposées, parmi les chefs-d’oeuvre absolus, les oeuvres de Malévitch (dont l’incunable Croix de 1915[14]), de la magnifique Katarzyna Kobro ou de Pevsner) :

“[Salle] 18. CONSTRUCTIVISMES

Dans la période qui succède à la révolution d’Octobre de 1917, l’art russe voit naître des courants très novateurs qui créent des ondes de choc dont la résonance est mondiale. L’abstraction radicale de Kasimir (sic!) Malevitch (sic!), profondément spirituelle, cherche à révéler l’essence du monde, au-delà des apparences contingentes. Tatline, Karel Hiller, les frères Pevsner et les frères Stenberg, conçoivent une activité artistique au service de la „production intellectuelle et matérielle de la culture communiste”. La peinture, la sculpture, mais aussi l’architecture, le design, la photographie et la typographie promeuvent la construction d’une société et d’un homme nouveau. Les artistes allient à la réflexion esthétique un intérêt marqué pour les matériaux, notamment le plastique ou le béton, et les procédés de construction.”

Cette présentation superficielle et, sur bien des points, inexacte est traduite en anglais… Ainsi, le suprématisme, qui n’est pas nommé, est présenté comme un « repoussoir » (spirituel!), quasiment confidentiel, expédié en une phrase, pour laisser toute la place à un constructivisme mondial. Si Tatline est bien un ancêtre du constructivisme soviétique et au-delà en Europe, il refusait d’être taxé de “constructiviste” et il n’a participé que marginalement au constructivisme soviétique constitué, tel qu’il s’est manifesté entre 1921 et 1927. Relisons les textes d’Anatoli Strigaliov qui fut le grand spécialiste de Tatline, en particulier son essai pour la grande rétrospective à la Städtische Kunsthalle de Düsseldorf :

“Pareillement à la majorité des avant-gardistes russes, Tatline plaçait de grands espoirs sur la technique (et sur la science, bien entendu). Mais la technique schématise la constitution des formes, aspire à l’uniformité des solutions, à la géométrie élémentaire des formes et à un „ groupe limité de matériaux”, évite les „formes de la courbure complexe”, se contente de la „relation stéréotypée” à l’égard de la „mise en forme des objets”[15]. Tatline critique „les constructivistes entre guillemets” qui „ont agrafé mécaniquement la technique à leur art”, mais qui, en fait, se sont mis à la stylisation décorative, se sont bornés à la mise en forme de livres („se sont mis à l’art graphique”). Les sans-objétistes (lisez – les suprématistes) sont les représentants des „formes primitives de la manière de penser l’art„ ce qui ne pouvait conduire à „la création d’un objet synthétique vitalement indispensable„[16].”[17]

L’ignorance des travaux du grand chercheur soviétique Sélim Khan-Magomiédov est flagrante. Dans son livre, traduit désormais en français, consacré à “la période de laboratoire” du constructivisme (1920-1921)[18], il étudie les origines de ce mouvement. Et dans ces origines, un rôle majeur a été joué, avant Tatline, par Malévitch qui, dès 1913, ne cesse d’affirmer que l’oeuvre d’art se construit, est construite. Souvenons-nous que la lithographie, exécutée d’après le tableau du Musée national russe de Saint-Pétersbourg Oussoverchenstvovanny portriet Ivana Vassiliévitcha Kliounkova [Portrait perfectionné d’Ivan Vassiliévitch Kliounkov, 1913], porte la mention manuscrite “Portriet stroïtélia oussoverchenstvienny” [Portrait perfectionné d’un constructeur) et a été insérée dans le recueil lithographié de Kroutchonykh Porossiata [Les porcelets] en 1913. Ce rôle constructeur apparaît ensuite dans les reliefs picturaux et les contre-reliefs de Tatline à partir de mars 1914.

Dans les écrits de Malévitch entre 1918 et 1921, on rencontre constamment les notions de construire, d’échafauder, de bâtir.[19] Et donc, si Malévitch a été dans les années 1920 un farouche adversaire du constructivisme, il est un de ceux qui ont préparé le terrain pour la naissance de cette nouvelle forme artistique.[20]

Sélim Khan-Magomédov tient compte de l’antagonisme des deux principaux courants des années 1920, le suprématisme et le constructivisme. Il a, par ailleurs, consacré tout un volume au suprématisme qui mériterait d’être traduit afin que les gens de musée et de nombreux historiens de l’art ne traitent pas l’auteur du Quadrangle noir de «constructiviste » ou ne mettent pas son suprématisme dans une nébuleuse appelée «constructivisme », ce qui est une aberration[21]

Sélim Khan-Magomiédov différencie de façon nette le suprématisme et le constructivisme, tout en notant qu’ils apparaissent aujourd’hui comme «complémentaires » :

« La particularité importante de ces deux mouvements consiste en ce que, bien qu’ils aient tous deux été conçus au sein d’une création concrète (la peinture), ils se sont éloignés autant l’un que l’autre des aspects concrets de la création artistique une fois parvenus au stade de la mise au point. On peut dire aussi qu’ils ont continué à se libérer de tout élément visuel concret de ce type de création (la peinture), jusqu’à ce qu’ils se soient affranchis de tout ce qui était le langage originel de la représentation, en expérimentant avec les formes spatiales de l’art. »[22]

Malévitch n’a jamais cessé de proclamer l’inexistence de l’objet en tant que tel et la force de l’énergie-excitation du sans-objet absolu. Le Suprématisme est la négation active du monde des objets, son but est de faire apparaître le monde sans objets et sans objet. Lorsque Malévitch parle d’un utilitarisme” suprématiste ou de l’économie comme 5ème dimension à l’ Ounovis de Vitebsk entre 1919 et 1922 ou bien à l’Institut artistique de Pétrograd-Léningrad entre 1923 et 1926, cela n’a rien avoir avec le fonctionnalisme ou le schématisme rationnels. L’économie et l’utilitarisme suprématistes visent à transformer le “monde vert des os et de la viande “[23], du “monde de la pitance”[24] dans un monde du désert, du vide, dirigé vers le dénuement de l’être. Même si le suprématisme est à la fois en action ontologique, une méditation sur l’être, cela ne signifie pas que les problèmes de la construction, que Malévitch a si fort désignés , comme nous l’avons dit plus haut, dès 1913, soient abandonnés. Le savoir-faire est essentiel pour le peintre (que l’on songe à l’intense travail pédagogique de l’école suprématiste pendant les années 1920 à l’Ounovis de Vitebsk et au Musée de la culture artistique à Pétrograd, devenu Ghinkhouk à Léningrad après la mort de Lénine en 1924.[25]

Mais la maîtrise artistique n’est pas le facteur principal ni le but de la création. Il doit se plier aux exigences du mouvement de l’être dans le monde; le matériau ne doit pas, comme chez les constructivistes, apparaître dans sa nudité squelettique, mais c’est plutôt la non-existence des formes et des couleurs qui doit être manifestée. C’est ainsi que les carrés, les cercles et les croix suprématistes ne sont pas des analogues des carrés, des cercles et des croix qui seraient dans la nature, ce sont l’irruption du non-être, l’irruption d’éléments formants et non informants d’une géométrie imaginaire. Le créateur du Quadrangle noir s’insurge contre la prédominance de la maîtrise artistique ou du “principe compositionnel”, tel que le définit Nikolaï Taraboukine dans son essai Le dernier tableau [1920]. Dans ses analyses du rythme, Taraboukine, qui sera un des porte-parole éminents du constructivisme soviétique, reste dans la dichotomie entre un intérieur (le rythme) et un extérieur (les schémas typiques de tel ou tel genre artistique).

Pour Malévitch, le rythme, qui est à l’origine de la vie en tant qu’excitation, doit apparaître en tant que tel. Il ne naît pas de rapport, de proportions, de symétries ou de dissymétries, il les origine. Le rythme se situe plutôt dans un centre de suspension entre l’apparent et l’inapparent. La “tempête” des couleurs et des formes, passe par “le condensateur de la raison qui réduit cette avalanche, cette force élémentaire pure, authentique, créatrice en formes figuratives, imitatives, mortes” :

“Cela est la même chose en sculpture, en musique, en poésie.

Il ne peut y avoir de maîtrise dans le divin poète, car il ne connaît ni la minute, ni l’heure, ni le lieu où s’embrasera le rythme.

Peut-être que ce sera dans un tramway, dans la rue, sur une place, sur une rivière, sur une montagne que se produira la danse de son Dieu[26], de lui-même. Là où il n’y a ni encre, ni papier et où il ne peut se souvenir, car à ce moment-là il n’aura ni raison, ni mémoire.

En lui commencera la grande liturgie.”[27]

Il n’est pas besoin d’aller plus loin pour montrer l’évidence que suprématisme et constructivisme se trouvent conceptuellement à des pôles l’un de l’autre. Cela s’est traduit très tôt dans l’opposition frontale de Malévitch et de Tatline dès l’exposition “0, 10″ en 1915-1916 à Pétrograd et ‘”Magasin”, organisée par Tatline à Moscou en 1916, où Malévitch se vit interdire d’accrocher des toiles suprématistes. Et en 1919, en pleine révolution bolchevique, l’historien de l’art Nikolaï Pounine, alors communiste-futuriste et exégète éminent de l’oeuvre de Tatline, pouvait tenir ces propos fielleux dans le journal du Narkompros [Commissariat du peuple à l’instruction] :

“Le Suprématisme s’est épanoui comme une fleur opulente à travers tout Moscou. Enseignes, expositions, cafés – tout est suprématisme. Et cela est très révélateur. On peut dire avec certitude que le jour du Suprématisme arrive, et ce même jour il doit perdre sa signification créatrice.

Qu’était le Suprématisme ? Sans nul doute, une invention créatrice, mais une invention purement picturale. C’était comme si le Suprématisme avait enclos toute la peinture du passé dans un cercle, par cela même il contenait en lui tous les défauts (aussi bien que les mérites) picturaux du passé. Un de nos artistes les plus puissants et sans nul doute le plus pur de tous, Tatline, a défini le Suprématisme tout simplement comme la somme des erreurs du passé et, du point de vue de Tatline, cela est profondément juste, conséquent et précis.

Le Suprématisme a pompé de l’histoire universelle de l’art toute la peinture imaginable et l’a organisée à travers ses éléments. Dans le même temps, il abstrayait cette peinture, la privant de chair, de matérialité (viechtchestviennost’), de raison d’être; voilà pourquoi le Suprématisme n’est pas un grand art, voilà pourquoi il est si facilement utilisable dans le textile, dans les cafés, dans les dessins de mode, etc. Le Suprématisme est une invention qui doit avoir une signification colossale dans les arts appliqués, mais ce n’est pas encore de l’art. Le Suprématisme n’a pas donné de forme. Bien plus, il est aux antipodes de la forme comme principe de la nouvelle ère artistique; le Suprématisme barre toutes les routes, c’est un cycle fermé sur lui-même, vers lequel ont conflué toutes les voies de la peinture universelle pour y mourir. Le Suprématisme est maintenant un mouvement artistique reconnu, il est reconnu parce qu’il est enraciné dans le passé ; le fait qu’il soit reconnu lui fait perdre sa signification créatrice. C’est K. Malévitch qui a été le grand inventeur du Suprématisme […].[28]

En cette même année 1919, s’était formé l’ Obmokhou [Société des jeunes artistes] qui de 1921 à 1923 fit trois expositions montrant des constructions aux formes minimales de Rodtchenko, des frères Guéorgui et Vladimir Stenberg, de Karl Ioganson, de Médounetski. Comme il a été dit plus haut, à l’automne 1921, ce fut l’exposition-manifeste du “Groupe de travail des artistes constructivistes”, à l’intérieur de l’Institut de la Culture artistique de Moscou (Inkhouk), “5×5 = 25” où Varvara Stépanova, son mari Rodtchenko, Alexandra Exter, Lioubov Popova, Alexandre Vesnine, montrèrent chacun 5 travaux qui ne devaient plus rien au chevalet mais étaient des oeuvres préparatoires pour des constructions dans l’espace et pour l’art de production. La “mort du tableau” (sanctionnée par les célèbres toiles de Rodtchenko Pur rouge, Pur jaune, Pur bleu en 1921), la fin de tout art “contemplatif” et la venue d’un art “actif”, proclamés alors, firent que l’on vit les artistes tourner en masse vers le design, les décors construits sur la scène théâtrale. Désormais, l’art se met au service de la technologie et de l’industrie. On pourrait même dire que, stricto sensu, il n’y a pas de “peinture constructiviste”, puisque le constructivisme est né précisément contre le tableau de chevalet. La “composition” est remplacée par la “construction”, le “tableau” par des “formes spatiales”, la création individuelle par la production, l’artiste par “l’ingénieur” ou “constructeur”, afin de transformer radicalement et modeler l’environnement. Travaillant le bois et le métal, faisant inlassablement des modèles de textiles, de vêtements, de meubles, de kiosques, développant considérablement la mise en forme des livres, l’art de l’affiche et du photo-montage. C’est au théâtre que le constructivisme trouva son application la plus naturelle.

======================

Dans cet essai, qui essaie de résumer les moments essentiels de l’opposition radicale entre suprématisme et constructivisme, bien que le suprématisme ait joué un rôle dans la naissance du constructivisme soviétique, puisque la “construction” a toujours été un facteur essentiel d’un mouvement qui était issu du cubisme, mais qui a fait, de façon totalement inattendue, un saut dans le sans-objet, l’abstraction radicale. Il serait intéressant de réfléchir au fait que Tatline, qui est revendiqué comme ancêtre du constructivisme soviétique, alors qu’il a toujours refusé de se ranger sous quelque “isme” que ce soit, a fait l’objet en 1921 d’un livre fondateur de son thuriféraire Nikolaï Pounine, qui porte le titre “Tatline, Contre le cubisme”[29]. Cet essai, très subtil, tout en affirmant l’importance capitale de la révolution cubiste, lui reproche, entre autre, son “individualisme esthétique”:

“Sur les débris de l’ancienne peinture, de la sculpture et de l’architecture, surgit un nouveau genre d’oeuvre d’art, qui s’efforce de peupler le monde, non pas avec des modèles, reflets individuels et magnifiques, mais avec des objets concrets, constitués par des éléments du monde plastique en des formes rationnelles qui, collectivement, synthétisent les forces créatrices et inventives de l’humanité.”[30]

On est, de toute évidence loin de l’ancien cubofuturiste et alogiste Malévitch qui, à la même époque, s’exclame :

” J’ai troué l’abat-jour bleu des limitations colorées, je suis sorti dans le blanc, voguez à ma suite, camarades aviateurs, dans l’abîme, j’ai établi les sémaphores du suprématisme.

J’ai vaincu la doublure du ciel coloré, je l’ai arrachée, j’ai mis les couleurs dans le sac ainsi formé et j’y ai fait un nœud. Voguez! L’abîme libre blanc, l’infini sont devant vous.”[31]

[1] Cf. Jean-Claude Marcadé, L’avant-garde russe 1907-1927, Paris, Flammarion, 2007, p. 269 sqq.

[2] Gérard Conio, Constructivisme russe, Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1987, t. I, p. 45-56, 247-256-264

[3] Cf. “The Realistic Manifesto. Gabo’s Translation”, in Gabo on Gabo. Texts and interviews(edited and translated by Martin Hammer and Christina Lodder), Forest Row, Artists. Bookworks, 200O, p. 28 : “[…] These are the five fundamental principles of our work and our constructive technique”. Cette traduction, qui tendait à montrer la priorité du Manifeste réalistedans la naissance du constructivisme a été reprise par la suite, en particulier dans les traductions françaises qui ont été faites à partir de cette traduction anglaise de Gabo et non à partir de l’original russe où l’on lit : “[…] Tels sont les cinq principes irréfutables de la création de notre technique de la profondeur.” [“Manifeste réaliste, 1920”, in Antoine Pevsner, Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre sculpté (par Élisabeth Lebon et Pierre Brullé), Paris, galerie-éditions Pierre Brullé, 2002, p. 25]

[4] Cf. Constructivism in Poland 1923-1936. Blok. Praesens.a.r., Lodz, Museum Sztuki, 1973

[5] Antoine Baudin, “Avant-garde et constructivisme polonais entres les deux guerres : quelques points d’histoire”, in : W. Strzeminski-K. Kobro, L’Espace uniste. Écrits du constructivisme polonais (textes choisis, traduits et présentés par Antoine Baudin et Pierre-Maxime Jedryka), Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1977, p. 13

[6] W. Strzeminski, “Notes sur l’art russe” [1922], in : W. Strzeminski-K. Kobro, op.cit., p. 44 (trad. Antoine Baudin)

[7] Ibidem, p. 50, 51

[8] Ibidem, p. 45, 50

[9] Cf. Andrzej Turowski, “L’art organisant la vie et ses fonctions…”, in catalogue Présences polonaises. Witkiewicz. Constructivisme. Les contemporains (éd. Dominique Bozo, Ryszard Stanislawski), Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1983, p. 140-145

[10] Que l’on me pardonne de m’auto-citer, mais je rappelle mes articles sur cette question : “Quelques réflexions sur le Suprématisme/Some Remarks on Suprematism”, in catalogue Suprématisme, Paris, Galerie Jean Chauvelin, 1977, p. 100-104; “Was ist Suprematismus? /What is Suprematism?”, in catalogue Malewitsch, Cologne, Galerie Gmurzynska, 1978, p. 183-186; “Qu’est-ce que le Suprématisme?”, in : K. Malévitch, Écrits IV. La lumière et la couleur, Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1981, p. 8-13; “Le Suprématisme de K.S. Malevič ou l’art comme réalisation de vie”, La Revue des Études Slaves, Paris, LVI/I, 1984, p. 61-77

[11] K. Malévitch, Le suprématisme, 34 dessins [1920], in Écrits, t. I, Paris, Allia, 2015, p. 253

[12] Jean-Claude Marcadé, “Quelques réflexions sur le Suprématisme”, op.cit., p. 100, 102

[13] Jean-Claude Marcadé, L’avant-garde russe 1907-1927, op.cit., p. 239

[14] Il n’est pas heureux que dans l’accrochage dont il est question la toile de Malévitch Croix, qui est en 1915 avec le Quadrangle (Galerie Trétiakov) et le Cercle (anciennes collections de Matiouchine, puis de Khardjiev, aujourd’hui collection privée) l’expression fondamentale du Suprématisme soit accrochée banalement comme une oeuvre ordinaire dans un environnement qui, de plus, est inadéquat et chronologiquement et conceptuellement.

[15] Vladimir Tatline, “Iskousstvo v tekhnikou” [L’art qui va dans la technique], in catalogue Vystavka rabot zasloujennovo diéyatelia iskousstv V.E. Tatline [Exposition des travaux du créateur émérite des arts V.E. Tatline], Moscou-Léningrad, 1932, p. 5 [Note de A. Strigaliov]

[16] Ibidem, p. 5-6

[17] Anatolij Strigalev, “Rétrospektivnaya vystavka Vladimira Tatlina”/”Vladimir Tatlin, eine Retrospektive”, cat. Vladimir Tatlin, Retrospektive (en allemand et en russe), Cologne, DuMont, p. 36-37

[18] Khan-Magomédov Sélim, L’Inkhouk : naissance du constructivisme (traduction de Françoise Pocachard-Apikian), Gollion, infolio, 2013

[19] Voir les occurrences des mots “construire”, “construction” et de leurs nombreux dérivés dans Kazimir Malévitch, Écrits, t. I, op.cit., p. 20-21 et passim (cf. Index rerum, p. 680)

[20] J’avais reproché au livre pionnier de Christina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (New Haven-London, Yale University Press, 1983), en voulant éviter précisément la confusion entre suprématisme et constructivisme, d’avoir totalement éliminé, dans le stade pré-constructiviste, toute la pratique artistique et théorique de Malévitch. : “Une fois établie l’antinomie fondamentale du constructivisme et du suprématisme, il reste encore à étudier ce qui de la pratique suprématiste a été retenu par le constructivisme” (“Le Suprématisme de K.S. Malevič ou l’art comme réalisation de vie”, op.cit., p. 62, note 3)

[21] S. O. Khan-Magomédov, Souprématizm i arkhitektoura : probliémy formoobrazovaniya [Le suprématisme et l’architecture : problèmes de la constitution des formes], Moscou, arkhitektoura-s, 2007 (l’ouvrage est abondamment illustré).

[22] Khan-Magomédov, Sélim, L’Inkhouk : naissance du constructivisme, op.cit., p. 17

[23] Kazimir Malévitch, “Ya prichol…” [Je suis parvenu à…] [1918], Écrits, t. I, op.cit., p. 139; voir aussi “Mir miassa i kosti ouchol” [Le monde de la viande et des os s’en est allé] [1918], in Ibidem, p. 145-147 et passim (voir les occurrences de “vert” et de “viande”, dans l’Index rerum).

[24] Kazimir Malévitch, Des nouveaux systèmes en art/De Cézanne au Suprématisme [1919-1920], in Écrits, t. I, op.cit., p. 227-229 et passim.

[25] Cf. Jean-Claude Marcadé, L’avant-garde russe 1907-1927, op.cit., p. 203-206, 221-225.

[26] Beaucoup de ces passages de “Sur la poésie” semblent avoir reçu une impulsion de Nietzsche, en particulier de Die Geburt der Tragödie; pour ce qui est de la danse, voir Le Crépuscule des idoles : ” […] L’art de penser doit être appris, comme la danse, comme une espèce de danse… Qui parmi les Allemands connaît encore par expérience ce léger frisson que fait passer dans tous les muscles le pied léger des choses spirituelles ! — La raide balourdise du geste intellectuel, la main lourde au toucher — cela est allemand à un tel point, qu’à l’étranger on le confond avec l’esprit allemand en général. L’Allemand n’a pas de doigté pour les nuances… Le fait que les Allemands ont pu seulement supporter leurs philosophes, avant tout ce cul-de-jatte des idées, le plus rabougri qu’il y ait jamais eu, le grand Kant, donne une bien petite idée de l’élégance allemande. — C’est qu’il n’est pas possible de déduire de l’éducation noble, la dansesous toutes ses formes. Savoir danser avec les pieds, avec les idées, avec les mots : faut-il que je dise qu’il est aussi nécessaire de le savoir avec la plume, — qu’il faut apprendre à écrire ? “, Götzendämmerung, “Was den Deutschen abgeht”, § 7

[27]Kazimir Malévitch, “Sur la poésie” [1919], in Écrits, t. I, op.cit., p. 188

[28] Nikolaï Pounine, “”À Moscou (Lettre)” [1919], in Kazimir Malévitch, Écrits, t. I, op.cit., p. 616

[29] Nikolaj Punin, “Tatlin contre le cubisme”, in Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, 1979, N° 2, p. 304-312 (traduction de Lucia Popova et Dominique Moyen)

[30] Ibidem, p. 312

[31] Kazimir Malévitch” Suprématisme” [1919], in Écrits, t. I, op.cit., p. 194

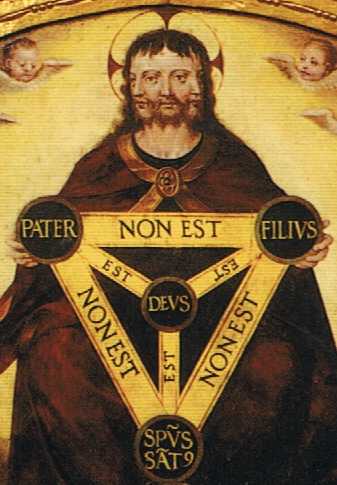

С ВОЗНЕСЕНИЕМ ГОСПОДНИМ!

By Jean-Claude on Juin 13th, 2024

Quelques photos du vernissage de l’ exposition de Simone Faïf chez Jean-Claude Marcadé le 19 mai 1992

By Jean-Claude on Juin 10th, 2024

Diaghilev et l’avant-garde russe

By Jean-Claude on Juin 7th, 2024

Diaghilev et l’avant-garde russe

Le fameux « Étonnez-moi ! » de Diaghilev à Cocteau représente-t-il, comme l’écrit Igor Markevitch (son dernier amour et découverte) « un caprice de blasé, parvenu du langage artistique »[1] ? Ou bien – et cela est plus vraisemblable- ne montre-t-il pas une caractéristique essentielle du génie de découvreur que fut celui de l’organisateur d’expositions, de concerts, de spectacles pionniers qui ont marqué tout le XIXe siècle ? Diaghilev était un résonateur des recherches esthétiques les plus novatrices de son époque et il s’est tout naturellement adressé aux peintres européens les plus originaux, faisant de ses spectacles le lieu d’expérimentation des tous les « ismes » de l’art. Et lui qui a eu l’ambition, depuis le début du XIXe siècle, de faire connaître au monde entier le renouveau artistique de son pays, la Russie, n’a pas manqué de faire appel à des représentants éminents de l’« art de gauche » russe et soviétique, ce que l’on a pris l’habitude d’appeler « l’avant-garde russe ». Ainsi les Européens purent se familiariser avec le primitivisme, le fauvisme, le cubofuturisme, le rayonnisme, l’orphisme et différentes formes du constructivisme.

Les décors et les costumes de Natalia Gontcharova pour l’opéra-ballet de Rimski-Korsakov Le coq d’or à Paris en mai 1914 marquent une rupture radicale avec l’esthétique antérieure des Ballets Russes dominée par l’art nouveau et le symbolisme. Avec Natalia Gontcharova, on assiste à la rutilance coloriste du primitivisme russe, imprégné de l’art des images populaires (les loubki), des icônes, du décorativisme propre à l’environnement d’une civilisation archaïque paysanne dominante, en particulier la chamarrure des étoffes. Sur cette structure de base venaient se greffer les principes plastiques les plus novateurs, cubofuturistes et rayonnistes, que l’artiste et son compagnon Larionov avaient montrés tout récemment à Moscou, Saint-Pétersbourg et Paris. Les rouges et les ors scintillent en une fête inconnue jusqu’alors de la palette picturale. À ce propos, Marina Tsvétaïéva a pu écrire :

« Le moment et le lieu sont venus de parler de Gontcharova en tant que passeur de l’Orient vers l’Occident – d’une peinture qui n’est pas seulement vieux-russe mais aussi chinoise, mongole, tibétaine, indienne. Et pas seulement de peinture. Notre époque prend volontiers ce qui est le plus antique et le plus reculé des mains d’un contemporain qui le renouvelle et le rapproche. »[2]

Le coq d’or inaugure la participation étroite de Gontcharova et de Larionov aux Ballets Russes jusqu’à la mort de Diaghilev en 1929.

Gontcharova exécuta une série de gouaches représentant essentiellement des sujets religieux, dans la pure tradition byzantine stylisée, pour le ballet sur musique de plain-chant, Liturgie, qui fut répété mais non réalisé en 1915.

Pour le ballet de Maurice Ravel Histoires naturelles en 1916, qui, lui non plus, ne fut pas réalisé, Larionov avait imaginé « des décors mouvants et des costumes mécaniques selon des formules plastiques manifestement futuristes. »[3]

Les scènes et danses russes du ballet Le soleil de minuit en 1915 permirent à Larionov de faire triompher ce néoprimitivisme par lequel il avait bouleversé, à partir de 1908, les données séculaires de l’art académique sur sol russe. Pour cette « fête du soleil », Larionov crée des costumes multicolores (à dominantes jaune, rouge, violette), la tête des personnages est ornée de fleurs fantastiques. Comme l’écrit Waldemar George :

« La vraisemblance est sacrifiée au rythme. Les gestes sont convulsifs. Les tons sont contrastés. D’immenses soleils sont peints sur les blouses bariolées des danseurs. Tous les rapports d’échelle sont modifiés. »[4]

Dans Les contes russes en 1917, c’est toujours la vieille Russie qui apparaît dans une synthèse d’archaïsme et de modernité, avec son alternance du burlesque et du magique. Le Méridional Larionov peut ici se laisser aller à son humour débridé en créant des êtres mi-humains mi-animaux à partir des personnages du folklore russe (la méchante Kikimora, le preux Bova Koroliévitch, la sorcière Baba-Yaga) ou ukrainien (le jeu de Noël koliadka). Pour les décors, l’artiste « avait peint les herbes aquatiques, les fleurs écarlates trempées dans le brouillard, l’isba éclairée par le demi-jour vert de la forêt où se déroulaient les histoires à faire peur. » [5]

Diaghilev poursuit la plongée dans les rutilements colorés du monde slave en confiant à Sonia Delaunay en 1918 les costumes du ballet Cléopâtre, qui avait été monté en 1909 dans des décors et des costumes de Bakst qui périrent par le feu en 1917. Les décors étaient de Robert Delaunay. Ainsi, c’est l’orphisme qui se matérialisa sur la scène. C’est aussi le prisme coloré ukrainien de Sonia Delaunay qui trouva là une expression étincelante avec le jeu des rayures et des cercles solaires. L’artiste a raconté comment elle voyait le personnage de Cléopâtre « apparaître comme une momie dont on déroulait au fur et à mesure les bandelettes. Celles-ci étaient toutes différentes les unes des autres […] Quand la momie était entièrement dépouillée, les projecteurs illuminaient la reine en costume solaire : des disques armant les seins, des cercles concentriques de toutes les couleurs et sertis de perles, rayonnant somptueusement autour du nombril du monde. Ces disques figurent sur un sarcophage du Louvre. »[6]

En 1921, Le bouffon (Chout), légende russe sur une musique de Prokofiev, dans la chorégraphie, les décors et les costumes de Larionov, fut un échec. Le décor mettait simultanément sur le même plan la fenêtre donnant sur le Nord, la porte qui menait au Sud, les murs de l’Est et de l’Ouest. Les costumes étaient en papier, toile cirée et carton. C’était le triomphe du cubofuturisme russe sur une structure de base néoprimitiviste. Waldemar George, qui a vu cette représentation, témoigne :

« Le bouffon (Chout) est un spectacle d’une verve étourdissante. Il allie à l’esprit d’innocence l’esprit de dérision. Des hypothèses de mathématicien, de géomètre sensible et de jongleur y affrontent les excès d’une imagination poétique délirante. »[7]

C’est encore à un représentant russe de l’avant-garde, Léopold Survage (Stürzwage), que Diaghilev s’adresse pour les décors et les costumes de l’opéra-bouffe de Stravinsky Mavra en 1922. Le peintre, qui avait été un des pionniers de l’abstraction avec ses Rythmes colorés à Paris en 1913, avait par la suite inventé une forme originale issue du cubisme qu’il définit ainsi : « Plusieurs formes géométriques simples, enchâssées les unes dans les autres, liées par un centre général, constituent pour l’œil un ensemble organique et centralisé, capable de suggérer la profondeur, sans creuser la surface plane à traiter, sans imiter le raccourci des objets par la perspective ordinaire. »[8]

À partir de 1922, Larionov et Gontcharova vont dépouiller leurs mises en scène des chatoyances orientales avec leur cubofuturisme rayonniste et primitiviste. À partir du ballet-bouffe Le renard (en réalité « la renarde ») , dans les décors et costumes de Larionov, on peut parler d’une émergence d’un certain « constructivisme ». Certes, Larionov, comme Yakoulov, a pu dire que les décors « construits » sur les scènes russes privées existaient depuis environ 1910 ; d’autre part, avant le constructivisme théâtral systématisé par Lioubov Popova et Varvara Stépanova en 1922 au théâtre de Meyerhold, il y avait eu, dès 1916, au Théâtre de Chambre de Taïrov, les décors construits d’Alexandra Exter, de Yakoulov, d’Alexandre Vesnine. En tout cas Le renard a connu deux versions, celle de 1922 et celle de 1929. La première est plus traditionnelle, dans le style du vertep ukrainien ; la seconde marque un pas vers une différenciation des personnages très sommaire (inscription de leur nom brodée sur leurs maillots), comme dans le théâtre médiéval ou élisabéthain. Danseurs et gymnastes se meuvent au milieu de trapèzes, de tréteaux et de plans inclinés. Écoutons Larionov : « Le perchoir sur lequel le coq était juché en 1922, s’élargit en 1929 aux proportions d’une plate-forme soutenue par un poteau et fixée au sol par quatre fils d’acier, sur laquelle venaient se poser alternativement les quatre personnages-danseurs et les trois personnages acrobates qui les doublaient sous le même costume. Cette plate-forme qui rappelait celles qu’emploient au cirque les acrobates était reliée au plateau par une échelle. Des cintres pendaient des fils de chanvre, dont les acrobates se servaient pour s’élancer des coulisses jusque sur la plate-forme en exécutant le pas–de-géant ou pour grimper aux cintres. »[9]

D’après Boris Kochno, Diaghilev demanda à Gontcharova pour le ballet Les noces, « mouvements chorégraphiques en quatre tableaux » de Stravinsky en 1923, de copier la coupe des costumes sur celle des vêtements de travail réglementaires que portaient les danseurs de la troupe lors des répétitions. On a là un écho de la prozodiejda, l’habit de production, introduit par Popova et Stépanova au théâtre de Meyerhold en 1922, pour détruire la couleur locale. Cependant, Gontcharova donnera une tonalité russe en allongeant les tuniques des danseuses en forme de sarafanes, tandis que les chemises des hommes recevaient une encolure à la russe. H.G. Wells nota que ce ballet, qui ne montrait pas des paysans déguisés en paysans mais simplement vêtus de noir et de blanc, était une transcription visuelle et sonore de l’âme russe. Dans un très bel article, Paul Dukas a noté que « comme spectacle [cette œuvre] brise tous les cadres, déroute toutes les classifications et se range d’emblée et délibérément à part de toutes les sortes de ballet connus […] Dans quel village de Russie vit-on jamais des noces semblables ? Sommes-nous même en Russie encore et dans celle même de la préhistoire ou dans un monde encore plus reculé, au-delà des temps et des réalités terrestres, dans ces limbes obscurs où des larves humaines célèbrent symboliquement leurs mornes épousailles ? »[10]

Désormais, les Ballets Russes proposeront des scénographies où l’élément constructiviste sera présent dans différentes variations, et ce sera le « réalisme constructeur » et le cinétisme de Gabo et de Pevsner, le constructivisme romantique de Yakoulov, le constructivisme surréalisant de Tchélitchev.

En 1926, quand ils abordent la mise en forme du ballet d’Henry Sauguet La chatte, Gabo et Pevsner ont une expérience de sculpteurs bien affirmée. L’utilisation de cercles et de rectangles en celluloïd crée une texture transparente totalement inédite. Ces formes étaient mises en mouvement par les danseurs qui les introduisaient sur la scène au fur et à mesure du déroulement de l’action. Ce cinétisme avait déjà été mis en œuvre par Popova à Moscou dans Le cocu magnifique. Le plateau et le rideau étaient en toile cirée noire. Kochno se souvient :

« La réalisation du décor de La chatte ne fut pas aisée. Gabo et Pevsner devaient exécuter eux-mêmes les parties métalliques de ce décor, entièrement construit, et leur apparition dans les paisibles hôtels et les pensions de famille monégasques où ils s’installaient pour travailler, provoquait une panique générale et faisait fuir les clients habituels. En les voyant circuler dans les couloirs, avec des lampes à souder, portant d’étranges masques de protection qui les faisaient ressembler à des scaphandriers, et en entendant le bruit infernal qui retentissait dans leurs chambres, la Direction les expulsait aussitôt après leur arrivée ».[11]

Diaghilev ne se contenta pas de cette incursion dans un constructivisme purement artistique et fit appel au peintre arménien Yakoulov pour les décors et les costumes du ballet de Prokofiev Le pas d’acier. Ce « ballet industriel » se substituait définitivement aux « cygnes mourants » et devait résumer aux yeux de l’Europe les conquêtes du constructivisme soviétique. La mise en forme de Yakoulov tenait compte de ses propres mises en forme chez Taïrov (Giroflé-Girofla, 1922), mais aussi des décors mécanistes de Popova pour Le cocu magnifique ou La terre cabrée chez Meyerhold (1922-1923). Ainsi, on trouvait chez Yakoulov des échelles, des plates-formes, des roues qui tournaient, des transmissions, des marteaux de toutes dimensions dont le bruit se fondait avec l’orchestre, des signaux lumineux qui oscillaient clignotaient et éclataient de feux et de couleurs. Les recherches scénographiques du Pas d’acier laissèrent des traces dans plusieurs réalisations ultérieures, aussi bien dans Les temps modernes de Chaplin (1936), que dans des ballets comme Nucléa, mis en forme par Calder (1952) ou L’éloge de la folie, mis en forme par Tinguely en 1967.

Enfin, peu avant sa mort, Diaghilev confie à Tchélitchev les décors du ballet de Nicolas Nabokov Ode. Tchélitchev avait travaillé en 1918-19 à Kiev dans l’atelier d’Alexandra Exter et exécuté ses premiers décors et costumes pour la scène, non réalisés, chez le metteur en scène Mardjanov. Puis le peintre a continué ses expériences théâtrales à Berlin où il est l’ami de Pougny en 1922-1923. Diaghilev a vu en 1923 son ballet Bojarenhochzeit (Noces de boyards) dont les éléments scéniques étaient dans un esprit cubiste-expressionniste.[12] Le travail de Tchélitchev pour Ode était d’une grande originalité : la boîte scénique, habillée de tulle bleu, était géométrisée à l’aide d’un réseau de fils métalliques qui créaient des objets, le tout étant traversé par la lumière d’une lanterne magique et des projections cinématographiques. L’emploi de projections cinématographiques sur la scène théâtrale était encore très nouveau. Picabia l’avait inauguré pour la mise en forme du ballet d’Eric Satie Relâche, en 1924[13] aux Ballets Suédois ; le peintre ukrainien Pétrytsky et le metteur en scène Ioura avaient, en 1925, utilisé le collage d’un écran de cinéma pour une adaptation théâtrale de la nouvelle de Gogol au Théâtre dramatique national Franko à Kharkiv[14]. Le critique français J.P. Crespelle a parlé, à propos de Tchélitchev du « style réticulé » de sa peinture, ce qui s’applique tout à fait aux décorations pour Ode. Le même critique assure que l’artiste russe « appartenait au monde des alchimistes, des astrologues et des magiciens » et que cette « magie […] s’efforçait à rendre sensibles les mystères et les drames de l’homme face au cosmos ».[15]

Ainsi, la scène des Ballets Russes a assimilé, en particulier grâce aux peintres issus de l’Empire Russe ou de l’Union Soviétique, les techniques scénographiques les plus récentes. Jusqu’au bout, Diaghilev resta à l’écoute des « bruits du temps ». Le recours aux expérimentations novatrices de l’avant-garde russe en est un témoignage éclatant.

Jean-Claude Marcadé

Le Pam, janvier 2009

[1] Igor Markevitch, Le testament d’Icare, choix d’écrits présenté par Jean-Claude Marcadé, Paris, Bernard Grasset, 1984, p. 153

[2] Marina Tsvetaeva, Nathalie Gontcharova, sa vie, son oeuvre, Paris, Clémence Hiver, 1990, p. 132 (trad. Véronique Lossky)

[3] Victor Breyer, in catalogue : Les Ballets Russes de Serge de Diaghilev. 1909-1929, Strasbourg, À l’ancienne douane, 1969, p. 141

[4] Waldemar George, Larionov, Paris, La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1966, p. 92

[5] Boris Kochno, cité par Victor Breyer, op.cit., p. 148

[6] Sonia Delaunay, Nous irons jusqu’au soleil, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1978, p. 78-79

[7] Waldemar George, op.cit., p. 100

[8] Survage, Essai sur la synthèse plastique de l’espace et son rôle dans la peinture [1920], in Ecrits sur la peinture, Paris, L’Archipel, 1992, p. 35

[9] Larionov, cité par Waldemar George, op.cit., p. 102

[10] Paul Dukas, «Noces d’Igor Stravinsky» [juin 1923], in Chroniques musicales sur deux siècles 1892-1932, Paris, Stock, 1980, p. 158, 159

[11] Boris Kochno, cité ici par Pierre Brullé dans le catalogue Pevsner 31 dessins, Paris, Galerie Pierre Brullé, 1998

[12] Cf. Donald Windham, «The Stage and Ballet Designs of Pavel Tchelitchew» [1944], in catalogue Pavel Tchelitchew 1898-1957. A Collection of Fifty-four Theater Designs c. 1919-1923, Londres, The Alpine Club, 1976, p. 4-6

[13] Cf. Denis Bablet, «Le photomontage de l’image à la scène», in Collage et montage au théâtre et dans les autres arts, Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1978, p. 100-101

[14] Cf. Valentine Marcadé, Art d’Ukraine, Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1990, p. 246

[15] J.-P. Crespelle, «Pavel Tchelitchew 1898-1957», in catalogue Hommage à Tchelitchew, Paris, Galerie Lucie Weill, 1966

Сергей Дягилев и русский авангард

Жан-Клод Маркадэ

Знаменитое восклицание «Étonne-moi!» («Удиви меня!»),

брошенное Сергею Дягилевым Жану Кокто – было ли оно, как

пишет Игорь Маркевич (его последнее открытие и последняя

любовь), «капризом скептика и парвеню

художественного языка»?

[ Igor Markevitch, Le testament d’Icare, choix d’écrits

présenté par Jean-Claude Marcadé, Paris, Bernard Grasset,

1984, стр. 153.]

Либо – и это кажется более вероятным – не было ли

оно проявлением свойства гения, первооткрывателя, устроителя

выставок, организатора концертов и новаторских спектаклей,

оставивших след на протяжении всего XX-го века? Дягилев был

камертоном самых новаторских эстетических устремлений своей

эпохи, и совершенно естественно, что он обращался к наиболее

оригинальным европейским художникам, превращая свои

спектакли в место для экспериментирования с художественными

«измами» всех мастей. Намереваясь с самого начала ХХ века

познакомить весь мир с художественными новшествами родины,

России, он не преминул обратиться с призывом к выдающимся

представителям «левого искусства», русского и советского – того

искусства, которое принято называть «русским авангардом».

Европейцы смогли при этом познакомиться с

примитивизмом, фовизмом, кубофутуризмом, лучизмом, орфизмом и контруктивизмом в разных его формах.

Декорации и костюмы Наталии Гончаровой для оперы-балета

Римского-Корсакова Золотой петушок, показанной в мае 1914

года в Париже, знаменовали собой радикальный разрыв с

эстетикой предыдущего периода Русского балета, где

господствовали символизм и Арт Нуво. Гончарова воплотила

колористический блеск русского примитивизма,

присутствовавший в народных картинках-лубках, в иконописи, в

декоративизме, присущем культуре древней и по преимуществу

крестьянской, для которой характерна, в частности, пестрота

тканей. На эту структурную основу прививались самые

новаторские пластические принципы, кубофутуристические и

лучистские, которые художница, вместе со своим спутником

Михаилом Ларионовым, незадолго до того продемонстрировала

в Москве, в Петербурге и в Париже. Красные и золотые цвета

сверкают в невиданной ранее праздничной феерии

красочной палитры. По этому поводу Марина Цветаева сумела

написать:

«Здесь время и место сказать о Гончаровой –

проводнике с Востока на Запад – живописи не столько старо-

русской: китайской, монгольской, тибетской, индусской. И не

только живописи. Из рук современника современность охотно

берет – хотя бы самое древнее и давнее, рукой дающего

обновленное и приближенное».

[Marina Tsvetaeva. Nathalie Gontcharova, sa vie, son

oeuvre, Paris, Clémence Hiver, 1990, стр. 132 (trad.

Véronique Lossky). Здесь цитируется по Марина

Цветаева, Наталья Гончарова. Жизнь и творчество;

Марина Цветаева, Избранная проза в двух томах. 1917–

-

Том первый, New York, Russica Publishers, 1979,

стр. 327.]

С Золотого петушка начинается

тесное сотрудничество Гончаровой и Ларионова с Русским

балетом, которое продолжилось до самой смерти Дягилева в

1929 году.

Гончарова выполнила также серию гуашей, преимущественно на

религиозные сюжеты, в стилизованном под византийскую

традицию стиле, для балета на церковную музыку под названием

Литургия, работа над которым шла в 1915 году, и который

остался неосуществленным.

Для балета Естественные истории 1916 года на музыку Мориса

Равеля, также не реализованного, Ларионов задумал

«движущиеся декорации и механические костюмы на основе

пластических формул ярко футуристического толка».

[ Victor Breyer, в каталоге Les Ballets Russes de Serge de

Diaghilev. 1909–1929, Strasbourg, À l’ancienne douane,

1969, стр. 141.]

Декорации и русские танцы балета Полуночное солнце 1915 года

дали Ларионову возможность реализовать свои

неопримитивистские устремления, ради которых он

ниспровергал, еще с 1908 года, вековые устои русского

академического искусства. Для этого «праздника солнца»

Ларионов создал красочные костюмы (с доминирующими

цветами желтым, фиолетовым и красным), а головы артистов

украсил фантастическими цветами. Как писал Вальдемар Жорж,

«правдоподобие было принесено в жертву ритму. Жесты были

конвульсивны. Тона – контрастными. Огромные солнца были

нарисованы на пестрых блузах танцоров. Все пространственные

взаимоотношения оказались модифицированы».

[ Waldemar George, Larionov, Paris, La Bibliothèque des

Arts, 1966, p. 92.]

В Русских сказках 1917 года представлена была старая Россия, но

в синтезе архаизма и современности, с чередованием волшебства

и шутовства. Южанин Ларионов мог здесь дать волю своему

юмору, ярко проявившемуся при создании фантастических

существ – полу-людей и полу-зверей – на основе персонажей

русского фольклора (например, злой Кикиморы, доблестного

Бовы-королевича и колдуньи Бабы-Яги), а также и украинского

(персонажей рождественских колядок, например). При создании

декораций художник «изобразил водоросли, пунцовые цветы,

покрывшиеся росой в тумане, избу, освещенную полуденным

зеленым светом леса, где развертываются устрашающие

сюжеты».

[ Борис Кохно, цит. по Breyer 1969, стр. 148.]

Дягилев настаивал на том, чтобы все было проникнуто сияющим

многоцветием славянского мира. В 1918 году он поручил Соне

Делонe сделать костюмы для балета Клеопатра, котoрый был

поставлен в 1909 году с декорациями и костюмами Льва Бакста,

погибшими потом при пожаре в 1917 году. Декорации были

выполнены Робером Делоне. Так на сцене материализовывался

орфизм. Украинская цветовая гамма Сони Делоне также

получила там блестящее воплощение, с игрой перемежающихся

солнечных окружностей и лучей. Художница рассказывала,

какой виделась ей Клеопатра – «она казалась мумией, с которой

постепенно снимают повязки. Все они разные. … Когда мумия

оказывалась полностью распеленутой, прожектора освещали

царицу, одевая ее в световой костюм: диски на груди,

концентрические круги всех цветов и с жемчугом как украшение

на животе. Эти диски есть на одном саркофаге в Лувре».

[ Sonia Delaunay, Nous irons jusqu’au soleil, Paris, Robert

Laffont, 1978, стр. 78–79.]

В 1921 году постановка Шута – русской фантазии на музыку

Сергея Прокофьева, с декорациями и костюмами Ларионова –

обернулась полным провалом. Декорации представляли

одновременно окно на Север и дверь на Юг, а стены были

Востоком и Западом. Костюмы были выполнены из бумаги,

клеенки и картона. Это был триумф русского кубофутуризма на

основе неопримитивизма. Жорж, который видел эту постановку,

свидетельствует:

«Шут – спектакль совершенно

ошеломляющий. В нем дух невинности перемешивается с духом

насмешки. Гипотезы математика, чувствительного геометра и

жонглера соревнуются здесь в эксцессах горячечного

поэтического воображения».

[Waldemar George 1966, стр. 100.]

И еще к одному представителю русского авангарда – Леопольду

Сюрважу (Штюрцваге) – обратился Дягилев с заказом на

декорации и костюмы: для оперы-буфф Игоря Стравинского

Мавра, в 1922 году. Художник, который был одним из пионеров

абстракционизма, показавшим в 1913 году в Париже свои

Цветные ритмы, впоследствии изобрел оригинальную форму

кубизма, которую определил следующим образом:

«Множество

простых геометрических форм, вставленных одна в другую,

связанных единым центром, на глаз кажущимся органичной

централизованной группой, способной намекать на глубину, но

без взламывания плоскости, без имитации ракурса предметов в

обычной перспективе».

[ Léopold Survage, «Essai sur la synthèse plastique de

l’espace et son rôle dans la peinture» [1920], in Écrits sur

la peinture, Paris, L’Archipel, 1992, стр. 35.]

Начиная с 1922 года Ларионов и Гончарова больше не

используют в своих мизансценах восточные радужные переливы

с их лучистскими и примитивистским кубофутуризмом. С

работы над балетом-буфф Лиса [Байка про Лису, Петуха, Кота да Барана] можно говорить о

возникновении некоего «конструктивизма» в декорациях и

костюмах Ларионова. Конечно, Ларионов, как и Якулов, мог

сказать, что «построенные» декорации уже существовали на

русских частных сценах уже около 1910 года. С другой стороны,

еще до театрального конструктивизма, разработанного Любовью

Поповой и Варварой Степановой в 1922 году в театре Всеволода

Мейерхольда, он уже существовал, с 1916 года, в Камерном

театре Таирова, где декорации делали Александра Экстер,

Якулов и Александр Веснин. В любом случае, постановка

Лиcица была осуществлена в двух версиях: 1922 и 1929 года.

Первая – более традиционная, в стиле украинского «вертепа»,

вторая – это шаг к дифференциации слишком обобщенных

персонажей (имя каждого наносится вышивкой на его трико), как

в средневековом или елизаветинском театре. Танцовщики и

гимнасты передвигаются среди трапеций, сеток и наклонных

плоскостей. Послушаем Ларионова:

«Насест, на котором сидел

Петух в 1922 году, в 1929 был увеличен до размеров платформы,

поддерживаемой столбом и закрепленной только с одной

стороны четырьмя стальными прутами. На платформе время от

времени размещались по очереди четверо персонажей-

танцовщиков и трое персонажей-акробатов, которые их

дублировали в тех же костюмах. Эта платформа, напоминающая

те, что используется в цирке акробатами, на поверхность ее ведет

лестница. Сверху подвешены пеньковые веревки, которые

акробаты используют для прыжка из-за кулис на сцену,

выполняя па-де-жеан, или для того, чтобы вскарабкаться

наверх».

[ Ларионов, цитируется у Вальдемара Жоржа в Waldemar

George 1966, стр. 102.]

Согласно Борису Кохно, Дягилев попросил Гончарову в 1923

году

для балета Стравинского Свадебка, («изображения хореографических движений в четырех картинах»),

скопировать покрой костюмов с одежды, которую танцовщики

труппы обычно носили на репетициях. В этом есть отголосок

«прозодежды» – производственной одежды, введенной Поповой

и Степановой в театре Мейерхольда в 1922 году, чтобы

упразднить местный колер. Тем не менее, Гончарова придаст

всему русский оттенок, удлинив туники балерин до длины

сарафанов и наделив блузы танцовщиков-мужчин застежкой как

у русской косоворотки. Г. Дж. Уэллс отметил, что этот балет, где

крестьян изображали не в крестьянской одежде, а одетыми

просто в белое с черным, был визуальным вополощением

русской души. В своей замечательной статье Поль Дюка заметил,

что «как спектакль [эта постановка] ломает все рамки,

переиначивает всякую классификацию и сразу демонстративно

занимает свое место вне всех известных видов балета. … В

России видели ли когда-нибудь в деревне подобную свадьбу?

Сами мы еще ли в России, в доисторический период, или в мире

еще более отдаленных веков, за гранью земного времени и

земной реальности, в темных чертогах, где человеческие

личинки символически празднуют свою мрачное

бракосочетание?».

[ Paul Dukas, «Noces d’Igor Stravinsky» [июня 1923], in

Chroniques musicales sur deux siècles 1892–1932, Paris,

Stock, 1980, стр. 158 и 159.]

В дальнейшем Русский балет предложит сценографию, где

конструктивистский элемент будет присутствовать в разных

вариациях, и это будет или «конструктивный реализм», и

кинетизм Наума Габо и Антона Певзнера, или романтический

конструктивизм Георгия Якулова, или сюрреалистический

конструктивизм Павла Челищева.

В 1926 году, когда Габо и Певзнер приступили к постановке

балета Анри Соге Кошка, они уже были известны как

скульпторы. Использование целлулоидных кругов и

прямоугольников создало совершенно необычную прозрачную

текстуру. Эти формы приводились в движение танцовщиками,

которые вводили их на сцену постепенно, по ходу действия.

Подобный кинетизм уже практиковался Поповой в Москве в

постановке Великодушного рогоносца. Сцена была покрыта

черной клеенкой, занавес также был из черной клеенки. Кохно

вспоминал:

«Построить декорации для Кошки было нелегко.

Габо и Певзнер должны были самостоятельно выполнить

металлические части этой декорации, полностью составной, и их

появление в мирных отельчиках и семейных пансионах Монте-

Карло, где они остановились на время работы, вызывало общую

панику и разгоняло традиционную клиентуру. Все видели, как

они кружили в коридорах с паяльными лампами в руках, в

странных защитных масках, которые делали их похожими на

водолазов, а когда, вскоре после их приезда, из их комнат стал

раздаваться еще и адский шум, дирекция выставила их вон».

[Борис Кохно цитируется здесь Пьером Брюлле; см. в

каталоге: Pevsner 31 dessins, Paris, Galerie Pierre Brullé,]

Дягилев не удовольствовался этим вторжением в область чисто

художественного конструктивизма и пригласил армянского

художника Якулова для работы над декорациями и костюмами к

балету Прокофьева Стальной скок. Этот «индустриальный

балет» решительно вытеснил «умирающих лебедей» и призван

был представить пред очи Европы достижения советского

конструктивизма. Здесь в оформлении Якулов учитывал свою

предыдущую работу у Александра Таирова (Жирофле-Жирофля,

1922 г.), но также и механистические декорации Поповой для

Великодушного рогоносца, как и для Земли дыбом у Мейерхольда

(1922–1923 гг.). И у Якулова были лестницы-стремянки,

платформы, крутящиеся колеса, трансмиссии, молоты всех

размеров, удары которых смешивались с музыкой оркестра,

световые сигналы, которые вибрировали, мигая и вспыхивая

огнем и цветом. Поиски сценографических решений для

Стального скока оставили след во многих последующих

постановках, не исключая Новые времена (1936 г.) Чарли

Чаплина и такие балеты, как Нуклея (1952 г.), который оформил

Кальдер, или Похвала глупости, поставленный Тэнгли в 1967

году.

Под конец, незадолго до смерти, Дягилев поручает Челищеву

создать декорации к балету Николая Набокова Ода. В 1918–1919

годах Челищев работал в Киеве в ателье Экстер, где и выполнил

свои первые декорации и эскизы костюмов для одной сцены в

постановке режиссера К.А. Марджанова [Марджанишвили], оставшейся

неосуществленной. Позже художник продолжил свои

театральные эксперименты в Берлине в 1922–1923 годах, где он

подружился с Иваном Пуни. В 1923 году Дягилев увидел

оформленный им балет Bojarenhochzeit (Боярская свадьба), со

сценическими элементами в кубистско-экспрессионистком

духе.

[ См. Donald Windham, «The Stage and Ballet Designs of

Pavel Tchelitchew» [1944], в каталоге Pavel Tchelitchew

1898–1957. A Collection of Fifty-four Theater Designs c.

1919–1923, London, The Alpine Club, 1976, стр. 4–6.]

Работа, сделанная Челищевым для Оды, была

исключительно оригинальной: сценическое пространство,

убранное синим тюлем, было геометризировано посредством

сети из металлических прутьев, которые создавали предметы, и

все было пронизано светом волшебного фонаря и проекцией

кинофильма. Использование кинопроекции на театральной сцене

было еще абсолютным новшеством. Францис Пикабиа обновил

этот метод для оформления балета Сати Отдых в 1924 году

[ См. Denis Bablet, «Le photomontage de l’image à la

scène», in Collage et montage au théâtre et dans les

autres arts, Lausanne, L’Âge d’Homme, 1978, стр. 100–]

-

для

Шведского балета. Украинский художник Анатоль Петрицкий и

режиссер Гнат Юрà использовали, в 1925 году, коллаж из

киноэкрана при оформлении театральной версии повести Гоголя

Вий в Государственном театре драмы им. Ивана Франко в

Харькове.

[ См. Valentine Marcadé, Art d’Ukraine, Lausanne, L’Âge

d’Homme, 1990, стр. 246.]

Французский критик Жан-Паул Креспель говорил, в

связи с Челищевым, о «сеточном стиле» живописи последнего,

что со всей полнотой применимо и к этой его театральной работе

над постановкой Оды. Тот же критик уверяет, что русский

художник «принадлежит миру алхимиков, астроголов и магов», и

что эта «магия … делает все для того, чтобы стали ощутимы

тайны и драмы человека, обращенного лицом ко Вселенной».

[ J.-P. Crespelle, «Pavel Tchelitchew 1898-1957», в

каталоге Hommage à Tchelitchew, Paris, Galerie Lucie

Weill, 1966.]

Таким образом, декорации к Русскому балету синтезировали,

частично благодаря художникам-выходцам из царской России и

из Советского Союза, новейшие театрально-декорационные

приемы. Дягилев в полной мере уловил «шум времени».

Использование им результатов новаторских экспериментов

русского ававнгарда свидетельствует об этом со всей полнотой.

Exposition Sabine Buchmann à Darmstadt, mai-juin 2024

By Jean-Claude on Juin 4th, 2024

Brüssel, 28. Mai, 2024

„Malerei Sabine Buchmann Brüssel; Gerry Keon, London; Margot Middelhauve, Darmstadt“ Atelierhaus-Vahle – Galerie C. Klein

Zeitraum 26. Mai 2024 – 29. Juni 2024

Bild Nr. 1

Titel: „Épanouissement – Entfaltung“ Format: 0,52 x 0,58 m

Material: Mischtechnik auf Reispapier 2023/2024

1

Bild Nr. 2

Titel: „Épanouissement – Entfaltung“ Format: 0,92 x 0,63 m

Material: Mischtechnik auf Reispapier 2023/2024

Bild Nr. 3

Titel: „Épanouissement – Entfaltung“ Format: 0,92 x 0,63 m

Material: Mischtechnik auf Reispapier 2023/2024

2

Bild Nr. 4

Titel: « La nature est un tableau vivant … Nous sommes le cœur vivant de la nature … « “Die Natur ist ein lebendiges Bild … Wir sind das lebendige Herz der Natur …” (Malewitsch) Format: 1,00 x 1,00 m

Material: Vinyl, Sand auf Leinwand

2024

Bild Nr. 5

Titel: « La nature est un tableau vivant … Nous sommes le cœur vivant de la nature … «

„Die Natur ist ein lebendiges Bild … Wir sind das lebendige Herz der Natur … ” (Malewitsch) Format: 1,00 x 1,00 m

Material: Vinyl, Sand auf Leinwand

2024

Bilder Nr.: 8 – 9 – 10

Titel: „Die Winterreise – Hommage à Schubert“ Triptychon

Formate: 3 x 0,80 x 0,80 m

Material: Sand, Vinyl, Seil auf Leinwand

2023

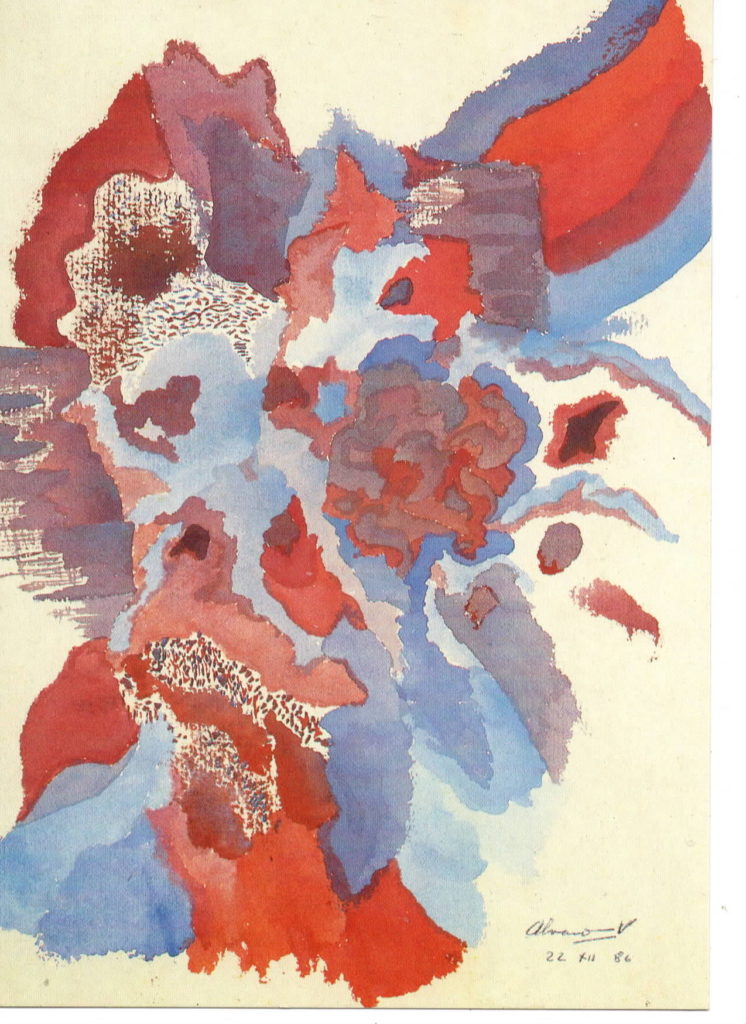

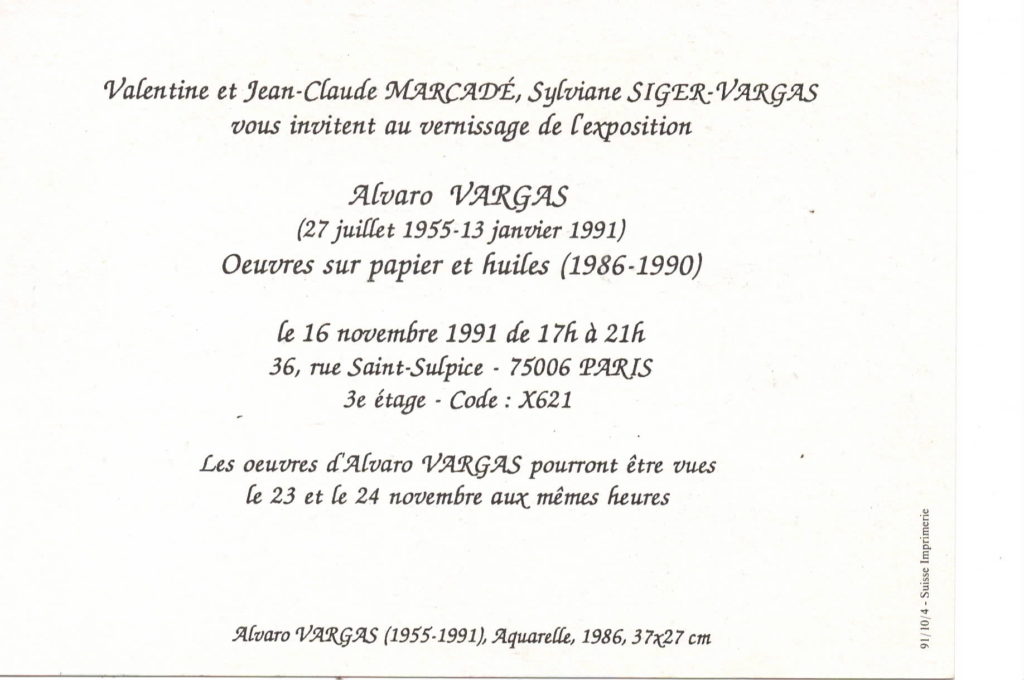

Exposition Alvaro Vargas à Paris en novembre 1991 (Archives V. & JCl. Marcadé

By Jean-Claude on Juin 1st, 2024

Exposition Alvaro Vargas à Paris en novembre 1991 (Archives V. & JCl. Marcadé)

(Visite de Katia Zoubtchenko, de son compagnon Stéphane qui a photographié l’exposition, du peintre ukrainien Volodymyr Makarenko et de sa femme Vika)

LE PHOGRPHE STÉP)HANE, COMPAGNON DE KATIA ZOUBTCHENKO, VIKA MAKARENKO, JEAN-CLAUDE MARCADÉ, VOLODYMYR MAKARENKO

A propos de l’auteur

Jean-Claude Marcadé, родился в селе Moscardès (Lanas), agrégé de l'Université, docteur ès lettres, directeur de recherche émérite au Centre national de la recherche scientifique (C.N.R.S). , председатель общества "Les Amis d'Antoine Pevsner", куратор выставок в музеях (Pougny, 1992-1993 в Париже и Берлинe ; Le Symbolisme russe, 1999-2000 в Мадриде, Барселоне, Бордо; Malévitch в Париже, 2003 ; Русский Париж.1910-1960, 2003-2004, в Петербурге, Вуппертале, Бордо ; La Russie à l'avant-garde- 1900-1935 в Брюсселе, 2005-2006 ; Malévitch в Барселоне, Билбао, 2006 ; Ланской в Москве, Петербурге, 2006; Родченко в Барселоне (2008).

Автор книг : Malévitch (1990); L'Avant-garde russe. 1907-1927 (1995, 2007); Calder (1996); Eisenstein, Dessins secrets (1998); Anna Staritsky (2000) ; Творчество Н.С. Лескова (2006); Nicolas de Staël. Peintures et dessins (2009)

Malévitch, Kiev, Rodovid, 2013 (en ukrainien); Malévitch, Écrits, t. I, Paris, Allia,2015; Malévitch, Paris, Hazan, 2016Rechercher un article

-

Articles récents

- Anciennes photos des archives, en vrac juillet 25, 2024

- Icône et avant-garde russes, deux faces majeures de l’art universel (2002) juillet 19, 2024

- EXPOSITION DES GOUACHES DE LANSKOY POUR “LA GENÈSE”, 36 RUE SAINT-SULPICE, 1990 juillet 12, 2024

- Malévitch et Mondrian, 2003 juillet 8, 2024

- Exposition de la “Valentine & Jean-Claude Marcadé Collection” à la Villa Beatrix Enea d’Anglet, décembre 2022-avril 2023 juillet 3, 2024

- Anciennes photos des archives, en vrac juillet 25, 2024

- “Préface” pour “Malévitch” en ukrainien février 18, 2013

- la désinformation sur l’Ukraine février 25, 2013

- vive les Toinettes du journalisme au “Monde”! mars 6, 2013

- de la malhonnêteté intellectuelle des moutons de Panurge du journalisme mars 17, 2013